Tolls and turnpikes

In 1905 the Hunts post was inundated with letters to their correspondence section over several months on the topic of St Ives bridges tolls. The levy was despised by tradesmen visiting St Ives. Charged to cross the bridges going into town, they were charged again to return home along the turnpike road south.

To learn about turnpike roads, the bridges' tolls and where the Duke of Manchester fits into the story, read on.

A brief history of roads in England

By the late 1600s roads were in an appalling state. With no major investment since Roman times, routes had reverted to little more than dirt tracks. Most journeys were short and local, the majority of goods transported by rivers and sea. Maintenance relied on a much resented medieval system of statute labour.

|

| The Great North Road approaching London before introduction of the turnpike system. The highway is deeply rutted and impassable in wet weather, spreading onto adjoining land. |

Turnpike roads

The first Turnpike Act was passed in 1663 to cover a section of the Great North Road from Wadesmill in Hertfordshire to Stilton in Huntingdonshire. The system proved so popular that by the early 1800s almost one thousand turnpike trusts controlled 22,000 miles of roads in England and Wales, about one fifth of the road network.

The routes were called turnpikes because the gate used to control access and collect tolls resembled barriers once used to defend against cavalry. In time some turnpike gates included side bars to catch farmers who attempted to only use the road between toll gates, diverting into fields to avoid payment.

Typical charges, with today's equivalent in brackets, were 1s (£4) for a coach or wagon, 6d (£2) for a cart, 1d (35p) for a ridden or led horse, 10d (£3.50) for a score of cattle and 5d (£1.75) for a score of sheep.

In the 1800s farmers were facing poor harvests and falling prices due to cheap foreign imports. When some trusts abused their powers and increased toll charges, dissatisfaction with the system grew. In 1839 groups of Welsh farmers dressed in women's clothing ripped down toll gates in what became known as the Rebecca Riots.

|

| A typical turnpike gate and toll house. |

With the introduction of railways resulting in less goods being moved by road, many turnpike trusts found themselves facing bankruptcy. Even those that survived had less funds for maintenance. Road standards again started to deteriorate. The 1888 Local Government Act created new County Councils, who became increasingly responsible for road maintenance, paid through the rates.

The Bury to Stratton turnpike road and tolls

St Ives' Monday market being a major venue for livestock sales, it's no surprise several turnpike roads passed by or through St Ives. The major route into the town was the Bury to Stratton turnpike road, running from near Ramsey to the Great North Road just south of Biggleswade.

St Ives was surrounded by toll gates. Travellers approaching from the south encountered two tolls in less than a mile, on the new bridges and St Ives bridge. The rights to these tolls were owned by the Dukes of Manchester, along with substantial land in the area. Charles Montagu was appointed the first Duke of Manchester in 1719 through his service to King George I.

It is unclear who was charged a toll. St Ives residents appear to be unaffected. There is comment in the 1905 letters that charges applied only to farmers and tradespeople. However, the letter that started the avalanche from Elliott Odams was about a motor car carrying the wife of Sir Frederick Harrison and two St Ives ladies. An altercation arose when they were stopped by the toll keeper.

The toll keeper was not in the employ of the Duke of Manchester, but bought the right to collect and benefit from the tolls. Edward Gurry was recorded as purchasing the let in the Hunts Post 4 October 1895 for £52, the equivalent of £6,500 today.

In spite of the strength of feeling about the St Ives tolls in 1905, and a general willingness by Huntingdonshire County Council to remove the tolls, they were still in place in 1913. Edward Gurry was toll keeper then (although he may not have been continuously since 1895) when the Hunts Post 13 June 1913 reported his summonsing of Ernest Wilderspin in the local court for assault following an argument over outstanding toll fees.

By the early 1900s the Duke of Manchester's family coffers were running on empty and William Montagu, the 9th Duke of Manchester, was an even bigger spendthrift than his father and grandfather. In 1918 he was declared bankrupt and over 5,000 acres of his Huntingdonshire estates were sold that year. It took another three years of negotiation before ownership of the new bridges and St Ives bridge, along with rights to charge a toll, was transferred to Huntingdonshire County Council. At last St Ives was forever free of toll.

The Bury to Stratton turnpike road and tolls

St Ives' Monday market being a major venue for livestock sales, it's no surprise several turnpike roads passed by or through St Ives. The major route into the town was the Bury to Stratton turnpike road, running from near Ramsey to the Great North Road just south of Biggleswade.

|

| Turnpike roads around St Ives (green), including part of the Bury to Stratton turnpike road (dark green). Toll gates are shown in red. |

It is unclear who was charged a toll. St Ives residents appear to be unaffected. There is comment in the 1905 letters that charges applied only to farmers and tradespeople. However, the letter that started the avalanche from Elliott Odams was about a motor car carrying the wife of Sir Frederick Harrison and two St Ives ladies. An altercation arose when they were stopped by the toll keeper.

The toll keeper was not in the employ of the Duke of Manchester, but bought the right to collect and benefit from the tolls. Edward Gurry was recorded as purchasing the let in the Hunts Post 4 October 1895 for £52, the equivalent of £6,500 today.

|

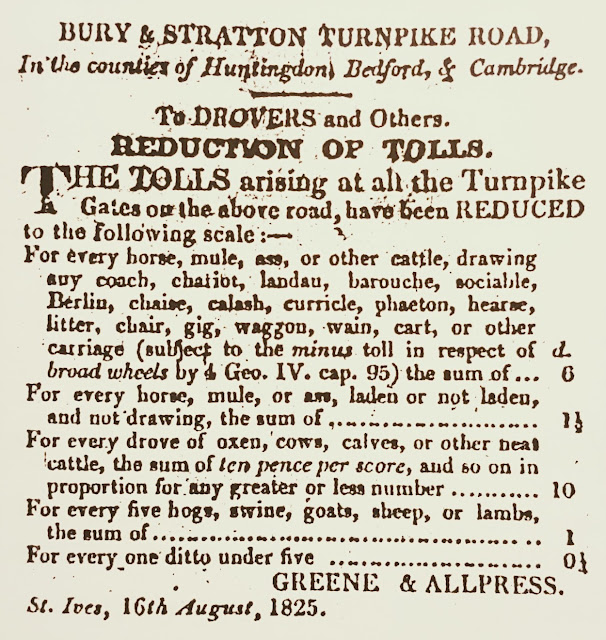

| Toll charges in 1825 |

By the early 1900s the Duke of Manchester's family coffers were running on empty and William Montagu, the 9th Duke of Manchester, was an even bigger spendthrift than his father and grandfather. In 1918 he was declared bankrupt and over 5,000 acres of his Huntingdonshire estates were sold that year. It took another three years of negotiation before ownership of the new bridges and St Ives bridge, along with rights to charge a toll, was transferred to Huntingdonshire County Council. At last St Ives was forever free of toll.

No comments:

Post a Comment