Sweep

Tradition has it that a chimney sweep brings luck. But there's a dark history behind the trade. Certainly dark for young sweep apprentices. Dark, dirty and deadly. Read on to learn about chimney sweeps and their apprentices, and to hear the life stories of the sweeps of St Ives.

Chimney sweeps

From the 1600s use of coal for domestic fires increased. At the same time chimney flues became narrower to increase upward draught. Several fires fed into a single chimney exit. More constriction meant sticky soot lined the flue. Harmful fumes could back up and pollute the home.

Some house owners resorted to DIY methods. Chucking geese or chickens down the chimney or dragging big bunches of holly up the chimney using a rope.

Regular visits from a chimney sweep became a safety necessity.

Sweep apprentices

For 200 years the standard method of cleaning a narrow chimney was to send a child apprentice up the flue. Some chimneys were only nine inches square. The apprentice shuffled upwards using back, elbows and knees.

Using a brush to clear the chimney above, soot fell on him. On reaching the top, the apprentice slid back down and collected soot in a bag to sell as fertiliser. A sweep could clean up to five chimneys a day.

Poor families sold children into slavery. Workhouse orphans were ready victims. Indentured for seven years, an apprentice was bound to the master sweep. Attempted escape meant an appearance in the local court and possible prison with hard labour. Supplied with bed and board, an apprentice got no wages.

It was common for the chimney to be hot from the last fire. Chimney sweeps encouraged their apprentices by lighting a fire in the grate, from which comes the term 'I'll light a fire under you'.

The children grew up stunted and disfigured. Many developed respiratory problems. Falls causing injury or death were common. Other risks were getting jammed in the narrow chimney or suffocating. The mortality rate for child chimney sweeps was very high.

Laws passed in 1840 and 1864 to stop the abuse were ineffective since they lacked means of enforcement. In 1863 Charles Kingsley wrote 'The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby'. His story of a little boy sweep who despises his cruel life helped the cause.

George Brewster was a 12-year-old chimney sweep. In February 1875 he got stuck up a chimney at Fulbourn Hospital in Cambridge measuring 12 inches by 6 inches. Rescuers had to pull down an entire wall to rescue him. He died shortly after. The authorities found the master sweep guilty of manslaughter.

George's death became part of an aggressive campaign. Another law enacted in September 1875 put an end to the use of young children as chimney sweeps. George was the last child to die in a chimney.

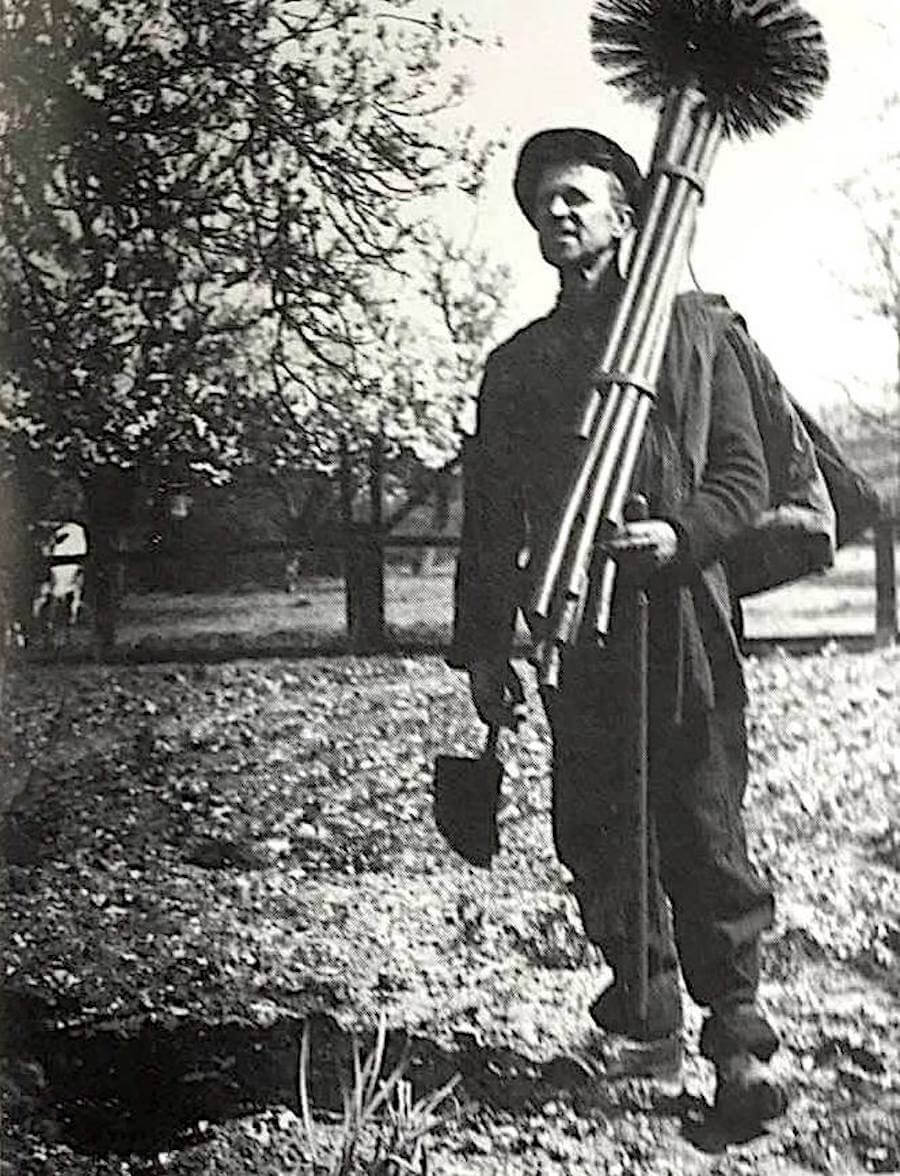

Inventions to aid the cleaning of chimneys came into being about this time. One of them, using brushes and canes to reach from the fireplace to the top of the chimney exit, is still used today. The image below shows St Ives sweep Herbert Pratt with such equipment in the 1930s.

|

| Herbert Pratt, a St Ives chimney sweep, c1930s. |

St Ives sweeps

DANIEL WINTERS was a sweep who in 1841 worked for his father from Croft's Yard, off Crown Street, St Ives. In 1846 Daniel accused William Bright of allowing a boy aged under 20 years to climb a chimney. William was another sweep from Godmanchester. The law prohibited persons under 21 years from going up a chimney. The magistrates gave William Bright the lowest fine possible. (Cambridge Chronicle & Journal 28 Feb 1846).

A few weeks later, William was up before the magistrates again. Having failed to pay his fine, William was heading for one month's gaol with hard labour. The magistrates expressed sympathy with William. How else were narrow chimneys to be cleaned? The newspaper stated Daniel himself used an under-aged boy to clean chimneys. (Cambridge Independent Press 21 Mar 1846).

The Winters probably were breaking the law. The 1841 Census shows three sweep apprentices living with the family, Elizabeth Harris, aged 20 years, and brothers John and Thomas White aged 15 years and 12 years. There is evidence all three were dead within ten years.

Business was good for the Winters family. By 1851 they ran the Bell Inn on The Waits, Daniel senior both publican and sweep. They employed Thomas Devine, a sweep aged 40 years born in Jamaica. Also their 10-year-old grandson Robert Wilkinson. Both were dead within ten years.

The Winters themselves didn't survive much beyond 1851. Daniel senior died that year aged 61 years. Daniel junior died in 1859 aged 48 years.

SAMUEL MAPPERLEY took over the Bell Inn on the death of Daniel Winters. Established as a sweep in St Ives from at least 1851, Samuel and family first lived in Alldens Yard. Living with the family was a sweep apprentice, William Cates, aged 10 years.

Once at the Bell Inn, not only did Samuel and his son Walter, aged 16 years, carry on their chimney sweep business. They also took the Bell Inn down market. With the family of six were twenty-one lodgers. The Bell Inn became known for cheap accommodation available to the poorest customers. Even tramps stayed there.

By 1891 Samuel had handed over the reins of The Bell Inn to his son in law, Arthur Hurl, a carpenter by trade. Samuel boarded at The Bell Inn. At the age of 74 years he still listed himself as a chimney sweep. Samuel died in 1911 aged 94 years.

HENRY WILKINSON was first a waterman by trade, in 1841 living in Magpie Alley close to his work at the Quay. By 1851 things must have been cosy at home. Henry's wife, Susannah, had given birth to seven children in ten years.

Living in the Bell Yard by 1861, Henry worked as a chimney sweep. His son Daniel, aged 15 years, was also a sweep. By 1871 Henry had followed Samuel Mapperley's lead. He was landlord of The Queen Victoria in West Street as well as a sweep. John, his 17-year-old son, was also a sweep. Another decade, another son employed as a sweep, this time George, aged 21 years.

None of Henry's sons stayed as sweeps for very long. Henry persisted, dying on the job sweeping chimneys at the Unicorn Hotel in 1887, aged 70 years. (Cambridge Independent Press 10 Dec 1887).

THOMAS COX was the most troubled of our sweeps. In 1871 he was a 20-year-old sweep lodging with and working for Samuel Mapperley. He was one of the poor lodgers at The Bell Inn.

Two years before Thomas was guilty of resisting the arrest of a prisoner. (Cambridge Independent Press 10 Jul 1869). In 1873 the authorities charged him with stealing money from his employer, Samuel Mapperley. (Cambridge Independent Press 19 Jul 1873). Six years later he handed himself in at Bourn. Thomas claimed he had stolen money and a jacket from Samuel Mapperley. This was untrue. It may have been a cry for help from a desperate man. (Cambridge Independent Press 1 Mar 1879).

In 1880 Thomas was sweeping a chimney in Fenstanton. On finishing, he called in at the Crown Inn for a drink. Thomas challenged one of three locals to toss a coin for beer. After three hours of coin tossing Thomas was in debt. When the landlady asked him to pay up for the beer he owed, Thomas refused. The landlady struck him several times. Much the worse for drink, he headed for the police station to complain. On returning the landlady hit him again with a broom. (Cambridge Independent Press 4 Dec 1880).

By 1881 Thomas lived in Prospect Place. With him was Elizabeth, shown on the census as his wife.

In 1882 Thomas tried to commit suicide. It seemed he had fallen on hard times, described as a 'tramping chimney sweep'. Lodging at the Hoops Inn, Chatteris, he started drinking laudanum. This was one of the most potent ways of consuming morphine. Also a common way to end one's life, three teaspoons being a fatal dose. Laudanum was available for treating everyday illnesses.

The woman Thomas 'co-habited with' managed to snatch the bottle from his hands before he took a fatal dose. Presumably this was Elizabeth. Thomas was in a dangerous state. The doctor applied a stomach pump. Excessive drinking was the cause of Thomas' malaise. Five weeks before Elizabeth had also attempted suicide. She threw herself in the river at St Ives. (Cambridge Independent Press 25 Feb 1882)

It appears Thomas may have had more success the following year. He died in 1883 aged 31 years.

No comments:

Post a Comment