George Game Day

One of the most gifted and controversial men to come from St Ives, George was a ferocious debater and political fixer. Landowners and businessmen celebrated his achievements. Working men's views were more mixed.

George achieved fame or notoriety locally and nationally several times in his life. He started a dynasty of town clerks and St Ives solicitors which still echoes. Read on to learn about the life of this complex man.

Upbringing and family life

Born in St Ives in 1796, George was the eighth of ten children born to Jonah Day and Frances Game. Half his siblings died in infancy. George's father was a St Ives tailor and pipe manufacturer. Imprisoned in the

Kings Bench Prison for debt, by 1824 Jonah reappeared as a successful auctioneer. Details of his auctions appeared weekly in the local newspapers. By then George was practising as a solicitor in St Ives. He also pleaded cases in court as an attorney. Father and son worked together. Jonah's adverts listed George as the contact.

In 1817 George married Johanna Clay Davenport. Johanna died the following year aged 24 years. In 1830 George married Mary Ann Newton.

George achieved success in both business and his marriage to Mary. In 1841 the family lived at Wych House, an imposing house

in the Bullock Market (today the Broadway). George's household included six children and five servants.

That success brought him the title Lord of the Manor of Colne, purchased from Joseph Sharpless in 1841. Along with rents came responsibilities. In January 1842 George gave every poor family in Colne a hundredweight of coal. The title stayed in the Day family for more than a century, at least until the death of George Dennis Day in 1948.

|

| George's signature. |

In 1848 George's second wife, Mary, died after a brief illness. By then there were eight children. Mary's obituary stated In her the poor of this parish have lost a most attentive and sympathising friend. George continued to live in the Bullock Market. Four of his children and three servants shared the house in 1851.

George married Mary Green in 1855, a farmer's daughter from Richmond, Surrey. By then he lived at Conduit Street, Mayfair, London, practising as a solicitor.

Family dynasty

The Borough Guardians appointed George as their clerk in 1837. George Newton Day, George's son and also a solicitor, took over after his father's death and became the first clerk to St Ives Town Council in 1874. His son, George Dennis Day, solicitor, succeeded his father in 1890.

George Lewis Day, solicitor, son of George Dennis Day, became Town Clerk in 1940. He was still serving in 1953. In that year he presented a mace to St Ives Town Council to mark his family's over 100 years and four generations of service to the town. It is still used today in formal ceremonies.

The family's long connection with St Ives' solicitors also lives on. George established Day and Son, solicitors, in the 1840s. The firm was still in business in 1989, 150 years later. In that year they amalgamated with Leeds Smith. Today they trade as Leeds Day Solicitors.

Faggot votersAfter the

Reform Act 1832 only male property owners aged over 21 years could vote in an election. This restricted the vote to 1 in 7 males.

The two main political parties in the early 1800s were the

Whigs and the

Tories. George supported the Whigs. Court hearings challenged registered voters to provide proof of entitlement. George was successful at removing many Tory voters from the register. He made enemies in doing so.

|

| Satirical print, 1832. Whigs hold the banner of Reform, battling Tories. |

One common abuse was when a landowner divided a single property into, say, four units. By transferring the title of each unit to four separate people he could create four new voters. Each would vote according to the landowner's wishes. They were called

faggot voters.

In 1835 George defended a court case alleging voter fraud. He acted for four men accused of being Whig faggot voters. One was his clerk, and all four claimed voter rights for land at

Colne, where George was Lord of the Manor.

The Court questioned the men's testimony. Of one it was said his evidence was delivered in a very unsatisfactory manner. The judge asked another if he had any explanation to give of his extraordinary evidence. There was an accusation of lying under oath. One man claimed he could not remember a conversation from that morning, his memory was bad.

George's enemies in the Tory party aimed to bring him down. He appeared at Huntingdon Assizes in 1836 for conspiring to place four persons on the list of voters. George put up a spirited defence. The court found him not guilty.

His supporters organise a subscription to cover George's legal costs and buy him a

piece of plate to commemorate his victory. In 1837 the great and the good from St Ives, the surrounding area and further afield, numbering 400, gathered to celebrate George's victory. They presented him with a cup containing 500 sovereigns, today's face value £52,000, and an

epergne. George gave a detailed account of the court case, reported throughout England.

In 1841 there was another attempt to defame George. For the annual election of workhouse guardians, George was the returning officer. His opponents accused him of maladministration and allowing ineligible persons to stand. Yet again George's opponents were unsuccessful. He was returning officer for the following year's election.

Support for the Corn Laws

Introduced in

1815, the Corn Laws blocked the import of cheap cereal grains such as wheat, oats and barley to the UK. They aimed to keep grain prices high to benefit landowners, who dominated membership of Parliament. People living in Britain's fast-growing towns and cities hated the Corn Laws.

When introduced, armed troops had to protect the Houses of Parliament. Food riots occurred across Britain when the harvest failed and prices increased in 1816.

It was clear landowners were acting in their own interests. The Corn Laws applied even when there was a food shortage. Their effect was that workers had to spend most of their income on bread. They had nothing left to buy manufactured goods, so factory workers lost their jobs. The economy spiralled downwards.

The

Anti-Corn Law League (ACLL) was a political movement established in 1838 that sought to abolish the Corn Laws. Its members argued they were morally wrong and economically damaging.

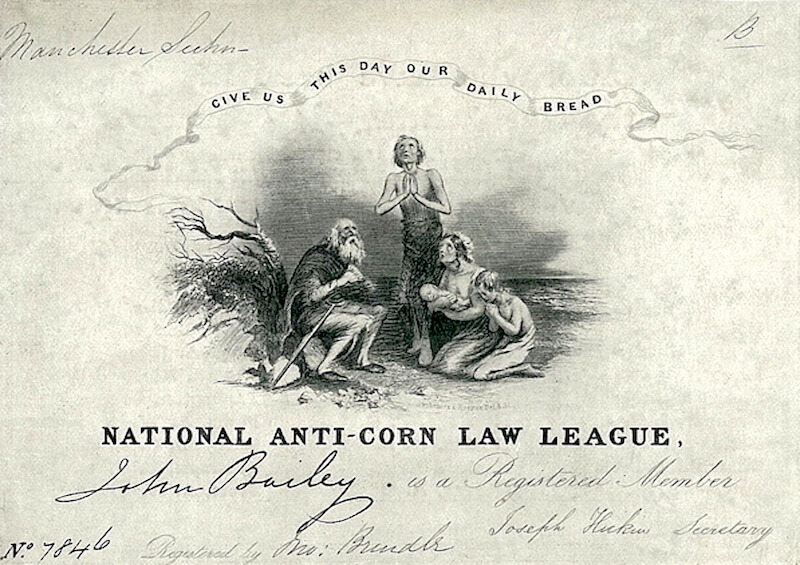

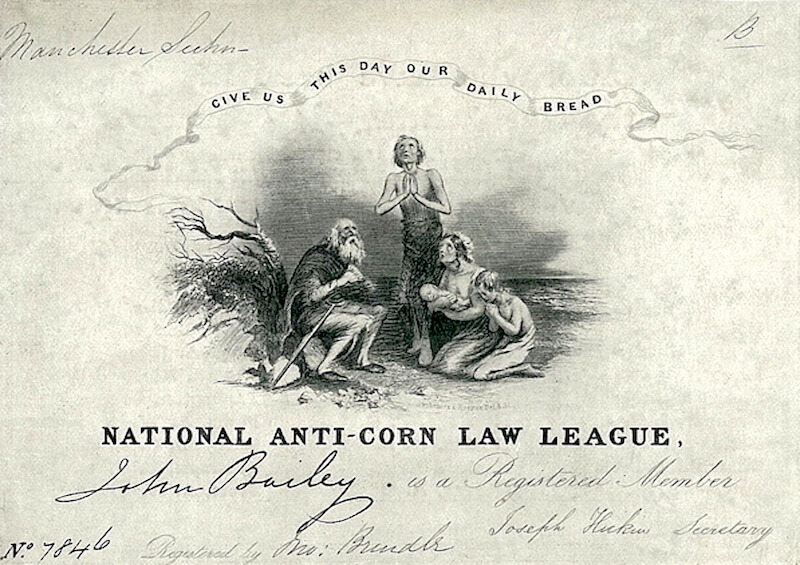

|

| Anti-Corn Law membership card. |

In 1843 leaders of the ACLL held a public meeting at Huntingdon. George was the principal speaker in opposition to the ACLL, thus supporting the landowners' cause. They were his most influential clients.

George so thoroughly defeated the ACLL speakers, newspapers throughout the country reported his speech. Immensely popular amongst farmers and landowners, the speech was advertised across the country as a pamphlet. The ACLL responded with their own pamphlet entitled 'A Refutation of Mr Day's Pamphlet, The Defeater Defeated'.

|

| Front page of George's pamphlet. |

Views on George's speech varied. Here are two examples.

At Huntingdon ... they (ACLL) have met with the most signal defeat, and now, like whipped curs, with their tails between their legs, they may run howling back to their kennels in Manchester and Salford...

I am extremely sorry, Friend Day, that thou has ... sold thyself to play the game of the landowners against the labourers, of the rich against the poor. Thou hast injured thyself and society by doing so.

George pushed his views home by writing to newspapers. He quoted contradictory quotations from speeches of

Richard Cobden, a founder and leading advocate of the ACLL. Local farmers and landowners recognised the contribution George made to their cause in a dinner at Huntingdon Town Hall.

The failure of the Irish potato crop in 1845 and the mass starvation that followed was the final straw to force a Government rethink. By the time of the dinner legislation had passed to reduce the effect of the Corn Laws.

St Ives railway

The 1840s were the boom years for railway construction. At the start of the decade railway lines in England were few and scattered. Within ten years an almost complete rail network existed. Most towns and villages possessed at least one railway connection.

The businessmen in St Ives weren't slow to spot an opportunity. George was the instigator. He'd been involved as early as 1835 to gain approval for a North and Eastern Railway from London. In August 1845, George formed a provisional committee for the St Ives and Wisbech Railway. He published a share offer within a couple of weeks and set capital at £500,000 with a share offer of 25,000 shares at £20 each. George didn't hang about!

A rail connection to Wisbech was important. It was the nearest port with access to the sea. Barges transported coal and other goods to St Ives. This was unreliable in winter when canals and rivers froze. A rail connection meant cheaper, faster and more reliable transport of goods.

Once all the shares were sold, the next stage was to apply to Parliament for a

Private Act. This gave private individuals or bodies rights. For example, to buy land along the proposed route of the railway. There were several hearings at which rivals or the public raised objections. Rivals objected in a quarter of applications. Many Private Acts failed at their first attempt.

In October 1845 a rival, the Huntingdon, Wisbech and St Ives Union Line published a share offer. It presented a genuine threat to the ongoing prosperity of St Ives. The rival sought to divert rail traffic away from St Ives to Huntingdon. At best St Ives would connect to the railway network by a branch line. The rival then struck this part of their plan out. The intention was to exclude St Ives from the rail network completely.

In the hearing in Parliament George claimed the rival bid planned construction 9 feet under the level of the Fens. This made it impossible to build. The rival's agent admitted a 'mere clerical error'. George's claims about their plans were correct. The agent attempted to challenge the plan presented by George Game Day. It transpired the agent used an out of date copy of George's plan. The Parliamentary committee threw out the rival bid.

|

| St Ives railway. |

In September 1846 The Eastern Counties Railway Company recognised Geroge's contribution to bringing the railway to St Ives. A banquet for 200 took place at the Crown Inn yard. The landlord erected a large marquee. Laurel leaves and flowers gathered from every garden in St Ives decorated the yard. At either end were two six-wheel locomotives. Constructed of laurel leaves, flowers and coloured lamps, one bore George Game Day's name, the other the word 'Union'.

Male diners sat in the marquee. In the gallery surrounding the courtyard were 80 lady guests. The lower classes were not forgotten. The following day all shops closed at 4.00pm. George paid for dinner at the Crown Inn yard with ale and tobacco provided. Music, dancing and the peal of the Parish Church bells followed. The event would be long remembered by the inhabitants of St Ives.

In December 1847 the former directors of St Ives and Wisbech Railway recognised again George's contribution. They arrived at his home to present him with an elegant gold cup filled with yet another five hundred gold sovereigns, funded by public subscription. The inevitable dinner followed at George's house.

In March 1848 the line opened from St Ives to Wisbech. About 700 passengers embarked from St Ives. At Somersham hundreds of residents watched the train arrive and 200 boarded. A band played, flags unfurled. Residents dined and planned a ball to celebrate the event.

Businesses closed at Chatteris. A band paraded through the streets and there was a public dinner. A further 1,300 passengers boarded. The stations at Wimblington and March were also crowded. By now the 33 carriages were full. To much disappointment no further passengers boarded.

Passengers arrived at Wisbech and downed a sumptuous dinner at the White Lion Hotel. Other hostelries seemed unprepared for the flood of visitors. Passengers stood by the riverside gazing at ocean-going vessels moored at the seaport. The return journey set off at 6.30pm, arriving in St Ives at 8.00pm.

George's death

George died in 1858 aged 63 years. By then he lived at 19 Gloucester Gardens, Hyde Park, London. His estate was valued at £30,000 (today almost £4m). He rests in the family vault in St Ives Parish Church graveyard.

Further reading

Below are links to copies of newspaper reports and original documents supporting the information in this article. Click any to view.

No comments:

Post a Comment