Theodore Watts-Dunton

High on the wall of Copleys Solicitors at the Red House, 10 Market Hill, St Ives, is the brass plaque shown below.

Born Walter Watts, for the first forty years of his life Theodore was an unassuming and unmarried St Ives solicitor living with his parents. For the last forty years barely a week went by without his name appearing in newspapers throughout the UK. When he finally released his major work of 20 years toil, to his complete bewilderment it was a literary success. Theodore married a 26 year old beauty when aged 73 years.

Read on to learn about this unassuming St Ivian, a literary critic, poet and author.

Upbringing

Born in Back Street, St Ives (today East/West Street) in 1832 as Walter Theodore Watts, he was the second of nine children. Theodore’s father, John King Watts, practised as a solicitor. His true love was science and he was well known in scientific circles in London. Theodore was fortunate to be the eldest son. His father took a decidedly classical inclination in naming his last three sons Erasmus, Octavius and Lorenzo.

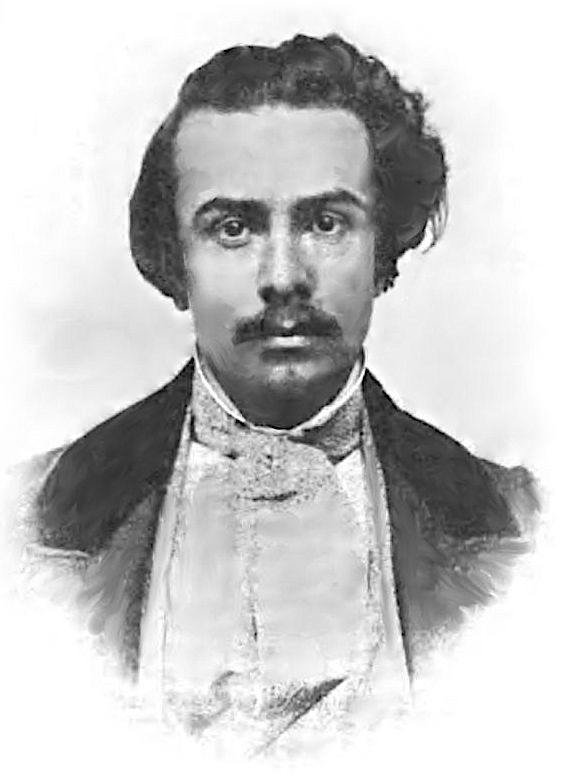

Theodore resembled his mother, Susannah Dunton. Small and dark in appearance, he was quick and alert with an active brain and poetic temperament. That active brain meant Theodore suffered from insomnia throughout his life, rarely sleeping over four hours. Yet he seldom showed signs of weariness.

Theodore’s love of letters came from his uncle, James Orlando Watts, also a solicitor who spent much of his life surrounded by books and manuscripts. Theodore attended a private school in Cambridge. When at home, he spent many evening hours reading books in his father’s library, joined by his parents.

From an early age Theodore wrote stories and poems. He wrote anonymous articles to the Cambridge Chronicle.

Closest to his younger brother Alfred, both studied law together. They qualified as solicitors on the same day.

By then the family home was The Red House, 10 Market Hill, St Ives, today occupied by Copleys Solicitors. The three solicitors, father and two sons, operated from home. Theodore and his father often travelled to London on business. They usually stayed at The Old Bell Inn in Holborn, close to the legal district. The Inn had strong literary connections. Charles Dickens and William Makepiece Thackeray were customers.

|

| Theodore as a solicitor. |

Theodore met and befriended novelist and critic Frederick Robinson and told him of literary ambitions, sending the draft of a novel which Frederick thought good. When Frederick offered to arrange publication Theodore hesitated, then declined, saying it wasn’t good enough. He had what he thought was a better novel on the go. That and an even better subsequent novel went the same way. Whatever Theodore produced fell short of his literary perfection.

London calls

Visits to London increased. Theodore socialised in London literary circles. His brother Alfred had ‘extraordinary social attractions’, which helped Theodore.

Two events made up Theodore’s mind to settle in London. His father’s St Ives solicitor's practise declined. Then Alfred died suddenly from heart failure caused by rheumatic fever suffered in early life.

Theodore moved permanently to London about 1870. He was already well known in literary circles that included Thomas Hardy, Robert Browning and Oscar Wilde. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the poet and painter, became a close friend after Theodore gave legal advice. Algernon Swinburne, considered for poet laureate, was even closer. Living near Theodore's chambers in 15 Great James Street, London, once introduced hardly a day passed when they didn’t dine together or meet in each other’s rooms.

Initially known as a conversationalist, Theodore's dialogue was described by Rossetti as being like that of no other person moving in literary circles. Theodore expressed new views in phrasings so polished that 'his improvised locutions were as perfect as fitted jewels’. Theodore's erudition, his remarkable literary instinct and brilliant discourse upon most subjects was already talked about.

From 1873 Theodore starting writing as a literary critic. Invited to all the best literary social events, by 1876 he was writing for the Athenæum. Theodore continued to develop his own work. Soon after moving to London he started writing 'Aylwin', a romantic novel.

Friendships

The association with Swinburne became more intense. Theodore took a lease on The Pines, 11 Putney Hill, London SW15. An alcoholic and algolagniac who enjoyed being flogged, when Swinburne's health deteriorated he moved in with Theodore and never left. Theodore prevented Swinburne's early demise from alcoholism. They went on daily walks and holidays together.

|

| Theodore and Algernon Swinburne (seated) in the garden of The Pines. |

Theodore was devoted to Rossetti, becoming his most intimate friend. Deeply depressed for the last decade of his life and addicted to chloral hydrate, Rossetti died in 1882. Theodore was present at Rossetti's death. Rossetti wanted Theodore to write his biography. It was never written.

Publication

Theodore's reputation as a literary critic grew. Barely a week went by without him being quoted in some newspaper. And although he continued to toil on 'Aylwin' and other works, none were released for publication until 1897. Theodore's first was 'The Coming of Love and Other Poems' published under the name of Theodore Watts Dunton.

In 1898 his romantic novel 'Aylwin' was published to critical acclaim. It was an immediate success. Aged sixty-six years, having toiled over the novel for more than 20 years, its success bewildered Theodore. By his death in 1914 it had sold 100,000 copies and was still in print in 1950. In 1920 it was made into a silent film. More publications followed.

Changes

At the age of 73 Theodore married Clara Reich in 1905. She was 26. Theodore first met Clara when she visited The Pines as a schoolgirl aged 16 with her mother. They became friends and before Clara was 21 they secretly considered themselves engaged.

|

| Clara Watts Dunton (née Reich), 1906. |

The death of Swinburne in 1909 left a great void. Unable to attend the funeral because of illness, Theodore found himself the sole beneficiary of Swinburne's will valued at £24,000 (today £3m). He was also the sole literary executor, responsible for the management of Swinburne's papers and unpublished works. Theodore was not in the best of health. He shrank with dismay at the labour involved in scrutinising Swinburne's manuscripts, letters and other papers exhumed from legal strong-rooms.

Theodore was also haunted by far a more onerous task. A biography of Swinburne must be undertaken. Friends expected it and Theodore was the best man for the job. Articles appeared in literary journals forecasting its publication, many originating from Theodore's friends. The biography never appeared.

Working method

Theodore was a perfectionist. Writing and rewriting multiple works from an early age, other than his critical articles nothing was published until his 65th year. Though a prodigious and untiring worker, he was unsystematic and a dreamer.

Theodore's habit of procrastination was the despair of his friends. On the day 'Alwyn' went off for publication Theodore was heard to say ‘If I had only kept back the proofs for another month, what a masterpiece I could have made of this novel!’

There was some justification to Rossetti's comment ‘Watts-Dunton seeks obscurity as other men seek fame’. Theodore was acutely sensitive to the views of others. A tepid review of anything he had written, let alone a hostile one, was sufficient to upset him for days.

He had no method in the arrangement of his letters and manuscripts. They were always in the utmost disorder, piled up in his study, covering the floor as well as the chairs and tables. But this confusion never worried him. He lived in a state of cheerful chaos.

On one occasion a friend who called looked round the room for an empty seat, and finding none stood somewhat embarrassed when asked to sit down. ‘Throw that heap of papers on the floor and help yourself to a cigarette. They won’t be touched. Nobody ever touches a scrap of anything in this room.’ said Theodore, pointing to an armchair covered in papers.

Last days

Even at the closing hour of his busy life Theodore's mental vigour was undiminished. He continued his work amongst a confusion of papers.

Scarcely an hour before he died Theodore was seated on a sofa in the drawing-room over a cup of tea, ready to dictate letters needing attention. His secretary had gone upstairs to the library to look for some manuscript, and on re-entering the drawing-room found Miss Theresa Watts seated near the sofa, believing her brother to be dozing. The secretary quickly realised the truth when she saw the expression on Theodore's face. He died in his sleep from heart failure without a movement, resting with the cushion supporting his head, as he often rested in the afternoon before continuing his work.

Theodore died in June 1914. He is buried at West Norwood Cemetery. A blue plaque is displayed at The Pines, Putney. Clara died in 1938.

It was said that Theodore's life work was not literature nor poetry, but friendship. His whole life was one long self-sacrifice of his own interests, his own fame, in the cause of his friends.

No comments:

Post a Comment