Cordwainer

In 1851 there were 37 cordwainers working in St lves, and as many shoe or boot makers. What was the difference between the two occupations? Why were there so many? And why not a single cobbler? Read on to find answers and learn about the life stories of three St Ives cordwainers.

What's the difference?

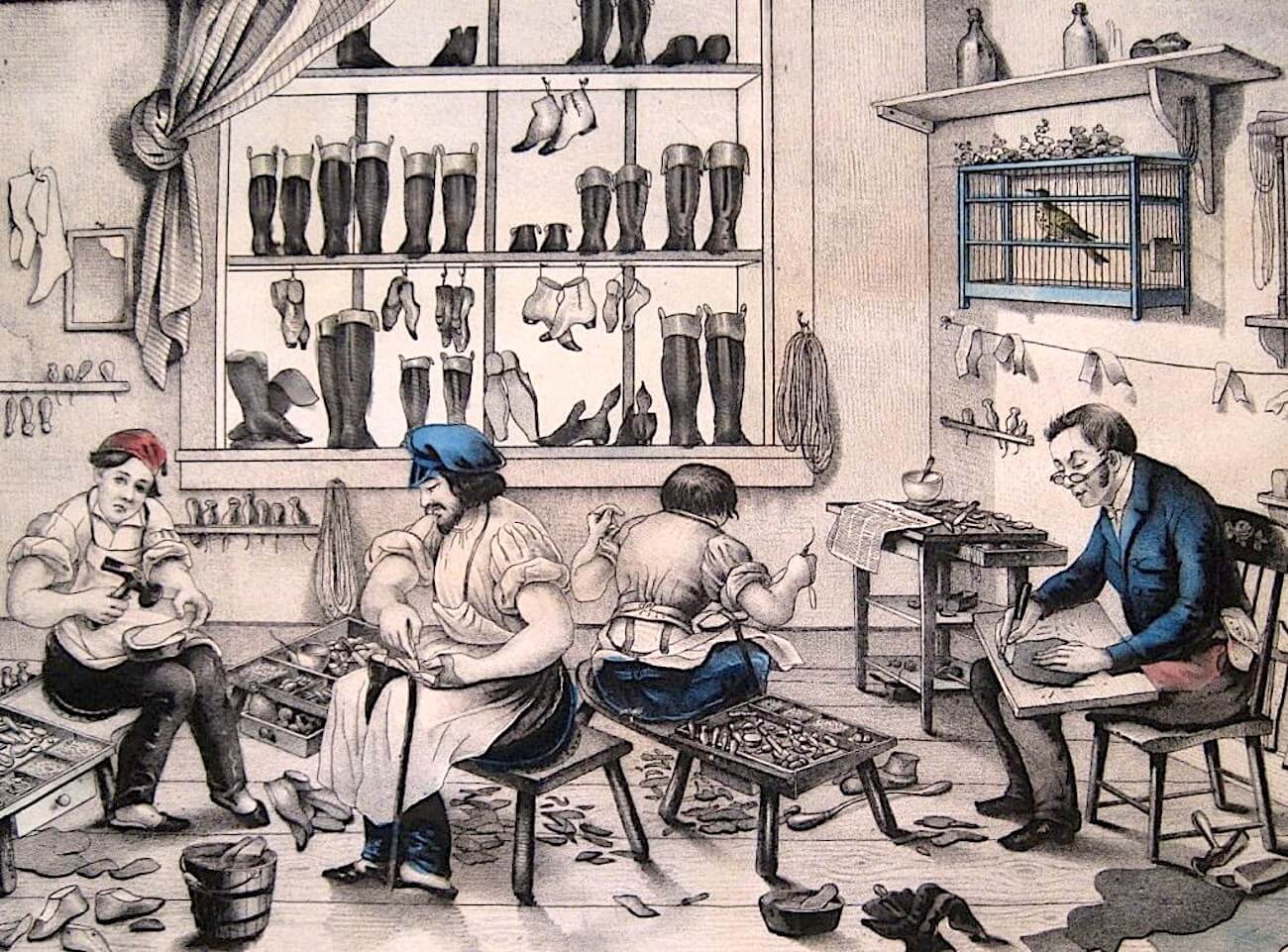

Cordwainer is an old English term for shoemaker, originally referring to a worker of leather from Cordoba, Spain. Cordwainers worked with new leather, making high-quality shoes. Cobblers handled old leather, repairing footwear or making cheap boots out of reclaimed material.

Used as far back as the 12th century, in St Ives shoemaker replaced cordwainer as an occupation from 1880 on. There were no cordwainers from 1901 onwards.

Why so many?

More than a hundred cordwainers, boot and shoe makers in 1851 St Ives meant there was one supplier for every twenty-seven residents. The pull of St Ives market was the reason there were so many.

Not only was the Monday market a magnet attracting customers from the surrounding county. It also drew in drovers from far and wide. Drovers who walked considerable distances herding their livestock to St Ives market, some from as far as Scotland and Ireland. Drovers in dire need of new boots.

No cobblers?

It's a sign how vibrant the trade was for new boots that there were no cobblers in St Ives. Anyone visiting the Monday market was unlikely to bring an old pair of boots for repair. They could get that done in their own village. If you had footwear-related business to transact, it would be to buy a new pair of boots where there was plenty of choice.

How did St Ivians get their boots repaired? At the cordwainers, though it would be an apprentice who did the work.

St Ives cordwainers

SAMUEL HILLYARD CHAMBERS was born in 1839 in the Cow and Hare Yard, one of the 49 yards of St Ives into which the town crammed its rapidly increasing early 1800s population. By 1851 the growing family moved to Green's Yard. Samuel was the second eldest of four sons and four daughters born to William Chambers and Catherine Hillyard.

In 1854 the Cambridge Independent Press reported Samuel appearing at the court in Priory Road charged with racing through the streets of St Ives, presumably on horseback. The previous week the authorities committed his opponent in the race, 'Mr Girling's lad', to 14 days in Huntingdon gaol. Samuel got off with £1 fine and expenses, today about £35.

The family were footwear makers to the core, with a business operating from Back Street (today East Street) in 1861. Next door Thomas Chambers worked as a shoemaker, possibly Samuel's uncle. Both Samuel and his father were cordwainers and his older brother William was for a time a boot maker. Boots were by far the more common footwear in the 1800s, and Samuel's younger brother Tom worked as a boot binder, stitching the leather uppers together. Samuel's mother was a shoe binder, showing the family sold high-quality goods.

Samuel married Alice Machin on Christmas Day 1863. It may seem a strange day to marry but was a popular tradition in the 1800s and early 1900s, more out of necessity than from a seasonal romance. Christmas and Boxing Days were traditional holidays and the only days young working couples could guarantee time off. It's a bit of a mystery how they met. Alice was a plate worker from Birmingham, 6 years older than Samuel. They married in the church of St Mary, Haggerston, London.

Possibly Samuel sought his fortune in London, met and fell for Alice and quickly married. They lived in Bethnal Green, where son Samuel was born in 1867. Another son, William Valentine, was born in 1869 at 2 Portman Terrace, Mile End Old Town, the house shared with another couple. By 1881 they shared 20 Queen Street, Mile End Old Town, with another family of three and their lodger.

Alice died in 1883, aged 48 years. In 1891 Samuel lived alone at 24 Doveton Street, Mile End Old Town, sharing with another single man and a family of four.

Samuel never found that fortune in London. Throughout his time there he worked as a boot or shoemaker, sharing accommodation in the smelly, cramped and run down East End of London, where life expectancy was barely 40 years. Samuel died in 1895, aged 55 years.

WILLIAM WALKER was born in 1833 in Easton, Huntingdonshire, where his father worked as an agricultural labourer. He was one of at least five children born to William and Sarah.

Aged 11 years or earlier, William started his lifelong calling, apprenticed to a bootmaker. Indentured and bound to his master, William got bed and board, but no wages. He gained his freedom through seven years of servitude. Attempted escape meant an appearance in the local court and prison with hard labour. Poor families sold their children into what was effective slavery and workhouse orphans were ready victims.

There's no sign William's family forced him into apprenticeship for financial gain. But no longer needing to feed the eldest son helped. Particularly when jobs on the land came under pressure as cheap Irish labour flooded through England, the impact of the Irish potato famine.

By 1851 William lodged with William Homer, a basketmaker, in Crown Walk, St Ives. His apprenticeship completed, William was a journeyman bootmaker. He still worked for a master bootmaker, but was paid daily and could change his employer. In subsequent years William stated his occupation as boot and shoemaker, including employing two apprentices in 1871, cordwainer in 1881, and back to bootmaker from 1891 onwards.

In 1853 William married Eliza Phillips. By 1861 William and Eliza and two daughters lived in Crown Yard, another of the 49 yards of St Ives. A son, Arthur, was born in 1865.

Business was good for the family by 1871. Not only did William employ two apprentices, one of whom lived with the family. Eliza had gone into business in her own right, as a straw bonnet maker. Eliza's business flourished, enabling her to employ a live-in assistant by 1881. Possibly the extra income allowed William to become more choosey about the work he took on. The 1881 census was the only time he showed his occupation as cordwainer.

Eliza's business acumen appears to have become the major source of income for the family by 1891. From straw bonnet maker she had blossomed into a full-blown milliner shop. She sold her creations directly to the public from premises in Bridge Street, between the popular Bryant's the Drapers and a butcher in the commercial heart of St Ives. William still made boots, described as 'neither employer nor employed', meaning he worked alone. Eliza was the employer, with a live-in milliner's shopwoman. They also had a live-in domestic servant.

It appears Eliza decided the cost of premises in Bridge Street wasn't worthwhile. By 1901 they were in East Street, William still working alone. Eliza's business continued to thrive as she employed her two granddaughters as live-in milliners.

Eliza died early in 1911. William was still living in East Street later that year, by then retired. Living with him was his daughter in law, carrying on the milliner business, and grandson.

William died in 1913. The Cambridge Independent Press published his obituary.

ROBERT SEE was born in Anmer, Norfolk, in 1810. He moved to Huntingdon aged about 4 years. By 1829 he was a cordwainer at Somersham, the year he married Elizabeth Stevens. A son followed in 1830.

In 1832 Elizabeth died. That same year a daughter, Elizabeth, was born and died. Possibly mother and daughter both passed away in childbirth.

Robert didn't hang about. Later the same year he married Catherine Bedford, a St Ivian. He didn't hang about family-wise either. Six daughters followed in quick succession over the next ten years.

In 1836 Robert was in Huntingdon gaol as an insolvent debtor, that is bankrupt. The authorities released him when Robert made arrangements with his creditors.

Catherine died in 1847. Within a year the Cambridge Independent Press reported Robert was again in Huntingdon gaol for a month with hard labour. He had left his four youngest children 'chargeable to the parish', meaning he had left them with no form of support. This was probably to work away, or because he was out of work and couldn't support them.

There's no trace of Robert in the 1851 census. Possibly he was on the road. There is a record of his four youngest children, in the St Ives Union Workhouse.

Robert had an illegitimate daughter in 1852 before marrying Mary Coker in 1856. In 1861 Robert, Mary and two daughters lived in Harrison's Lane, St Ives, one of the lost lanes that lead off what is now East Street.

Robert was back in Somersham in 1871, with Mary and their granddaughter. They also had journeyman shoemaker as a boarder, indicating business had improved. Robert was still working in 1881, aged 70 years.

Robert died in 1890, aged 79 years. He left Mary an estate worth £726, today valued at £95,000. This is a surprising legacy. Clearly, business was good in the latter part of Robert's life.

No comments:

Post a Comment