The Idiots Act 1886 gave the following definitions:

Read on to understand how the community provided care, and learn about the lives of St Ivians for whom those terms were used.Idiots - Persons so deeply defective in mind from birth or from an early age as to be unable to guard themselves against common physical dangers.

Imbeciles - Persons in whose case there exists from birth or from an early age mental defectiveness not amounting to idiocy, yet so pronounced that they are incapable of managing themselves or their affairs, or, in the case of children, of being taught.

|

| Hogarth's print of Bedlam Lunatic Asylum, 1735. |

The first and most famous private madhouse was Bethlem Royal Hospital, or Bedlam as it became known. Built in 1676, within a hundred years it was the top tourist attraction, with thousands of Londoners each year paying to view inmates. Wardens chained patients to their beds or to the walls. There was a lack of clothing and heating. Rats added to the misery. Violent inmates shared cells with those needing calm. Purgative cures were typically the solution to all ailments.

Legislation

The Madhouses Act 1774 required all madhouses to be licenced and subject to an annual checkup. Inspectors kept a register of all those confined.

The Lunacy Act 1845 compelled local authorities to build lunatic asylums. By 1859, of the 36,000 people classed as lunatics in England, all but about 7,000 were in workhouses and a similar number 'with friends or elsewhere'.

|

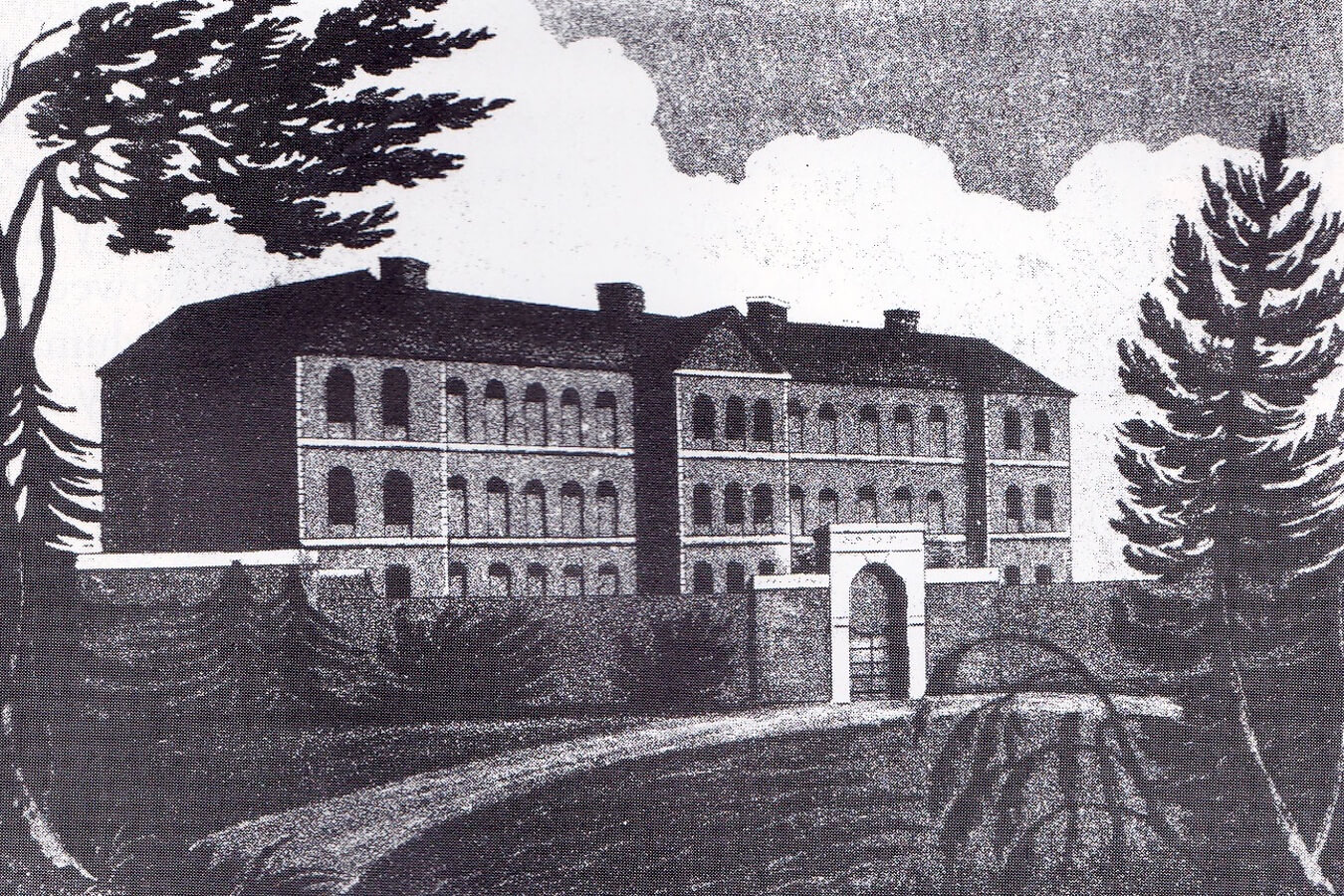

| Bedford Lunatic Asylum, 1812. |

Bedford Lunatic Asylum

The earliest St Ives residents placed in formal care were sent to Bedford Lunatic Asylum. Opened in 1812, it was one of the earliest built after the Madhouses Act 1774. By 1837, a facility planned for forty patients was receiving inmates from Huntingdonshire, Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

The 1841 Asylum census named 116 patients, but did not show place of origin.

The 1851 census listed 264 patients. Only initials were recorded. For two male and two female patients not even their names were known. There was a surprising number of patients from St Ives, totalling 17. This was 6.5% of the total, six times as many as could be expected. Why was this?

St Ives Union Workhouse was bursting at the seams in 1851. More typically housing under 100, in 1851 the Workhouse inmates totalled 320, a quadrupling of numbers in the ten years from 1841.

Developments in agriculture meant farmers needed fewer workers. Once a farm labourer lost his job, the tied cottage went as well and the family were homeless. The Irish Potato Famine drove starving Irish to England seeking work, reducing wages for day work on farms. With deprivation causing increased anxiety in the St Ives population and no room at the workhouse, those needing care went straight to Bedford Lunatic Asylum.

The 1851 Committee of Visitors Report is fastidious in detail. Fully 95% of patients were classed as 'incurable'. In some cases, symptoms causing the commitment had existed just a few weeks prior to admission.

Long before it closed in 1860, Bedford Lunatic Asylum was overcrowded, cold and damp. The cemetery was also full to bursting. Patients were transferred to the more commodious Three Counties Asylum, opened that same year.

The following lists available details of the 17 St Ives patients from the 1851 census.

'AS', 37 year old unmarried female servant

'AS', 59 year old married druggist's wife

'CN, 59 year old unmarried female servant

'EF', 54 year old married labourer's wife

'EH', 28 year old married bricklayer's wife

'GP', 26 year old single farm labourer

'HA', age unknown but estimated as 50 years, married carpenter

'HS', 43 year old married bricklayer

'JF', 34 year old married horse dealer

'MAC', 32 year old unmarried female servant

'MW', 41 year old married schoolmaster

'RO', 49 year old unmarried carrier

'SG', 64 year old unmarried female of unknown occupation

'TC', 31 year old unmarried shoemaker

'WB', 44 year old married tailor

'WFS', 29 year old unmarried grocer

'WS', 37 year old unmarried labourer

|

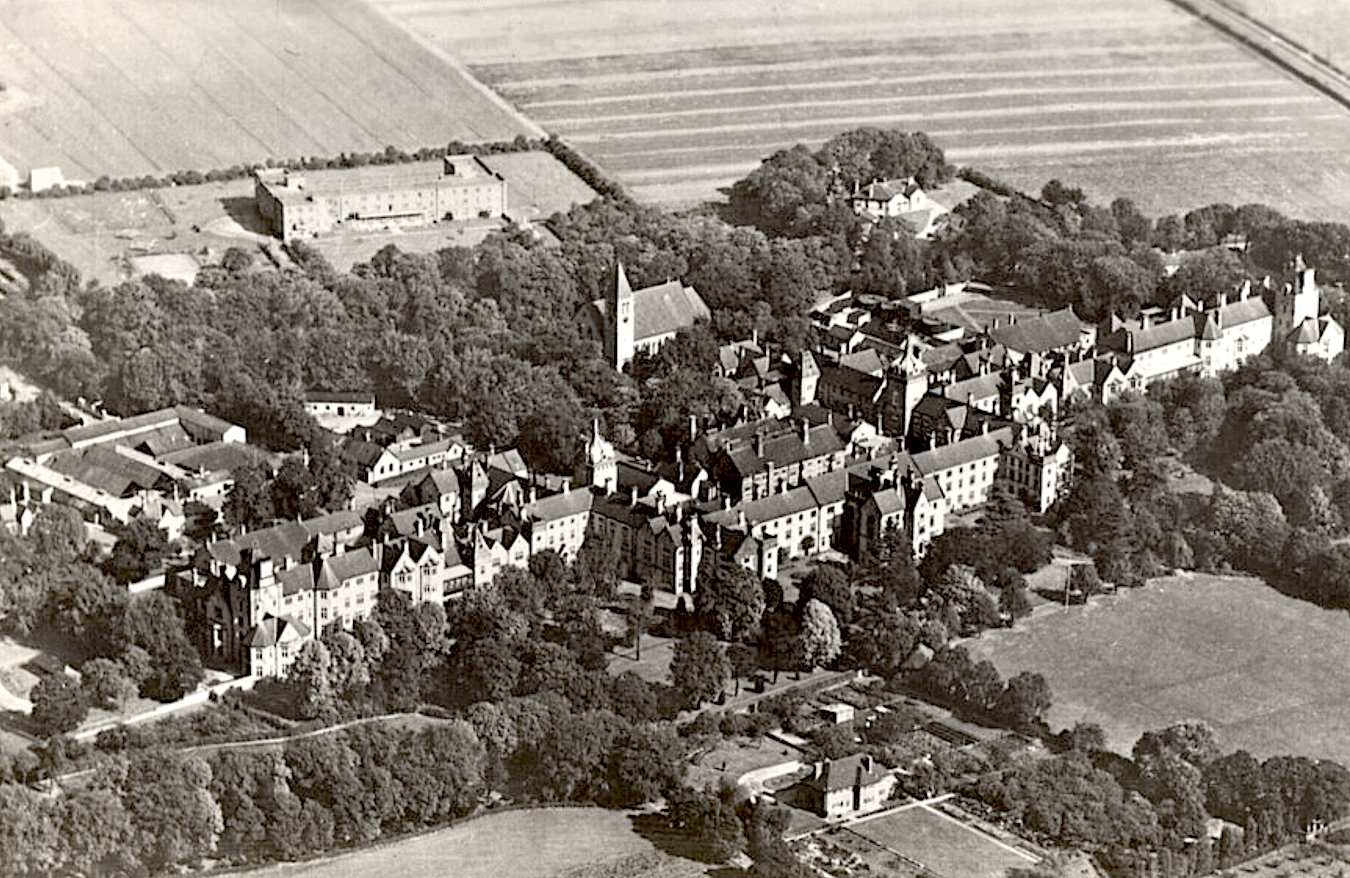

| Three Counties Lunatic Asylum. |

Three Counties Lunatic Asylum

The 1861, 1881 and 1901 Asylum censuses only gave initials and no place of birth. For the 1891 census all 1,056 inmates showed their place of birth as 'not known', untrue for the majority.

The 1871 census listed 525 inmates. The youngest was a male aged 9 years, the youngest female 11 years. The majority of inmates were of middle or old age. There were four St Ivians.

The 1874 Committee of Visitors Report also contained much detail of the patients. Page 37 shows the locations from which patients came in the year. St Ives sent 42, the seventh highest out of thirty-two, and the highest for Huntingdonshire.

In the 1911 census there were 948 inmates listed. For a considerable number of inmates their place of birth was genuinely unknown. There were four St Ivians.

The following lists available details of St Ives patients in the Three Counties Lunatic Asylum.

1871

'EH', 48 year old wife of a bricklayer, lunatic (also Bedford Lunatic Asylum 1851)

'MS', 40 year old wife of bricklayer's labourer, lunatic

'TC', 51 year old married shoemaker, lunatic (also Bedford Lunatic Asylum 1851)

'WFS', 49 year old unmarried grocer, lunatic (also Bedford Lunatic Asylum 1851)

1911

'AK', 30 year old single journeyman baker, 'lunatic at 29'

'CP', 25 year old single journeyman tailor, 'deaf and dumb from birth, congenital idiot'

'GB', 38 year old single farm labourer, 'lunatic at 8'

'TW' 39 year old single farm labourer, 'lunatic at 30'

Arthur Kidman was 'AK', born in St Ives in 1882 to John and Hannah. He was the eldest of two sons and two daughters. The family home, and from where John ran his baker's business, was in The Waits. Arthur followed his father's trade as a baker.

Charles Philpott was 'CP', born 1885 to John and Susannah, the second youngest of three sons and two daughters. The family moved from Stansted, Essex, to St Ives just before Charles' birth, living in Campion's Yard, one of the 49 Yards of St Ives. John and Susannah had a further four children in the decade to 1901, but there's no trace of Charles in the 1901 census, certainly not with his family.

In 1904, aged 19 years, Charles appeared in the local court, charged with assaulting Alice Landles, the 35 year old wife of a printing foreman living in Cromwell Terrace, St Ives. There's no indication whether the assault was unprovoked, or Alice Landles goaded Charles into action. Either way, once violence was thought a feature of behaviour there was only one outcome. The 'home where he could be educated' was the Three Counties Asylum. Described as 'deaf and dumb' in the 1891 census, the Asylum recorded Charles as a 'congenital idiot' in the 1911 census. It's likely he spent the rest of his life in the Asylum.

|

| St Ives Union Workhouse, c1890. |

St Ives Union Workhouse

The 1851 census was the first to record 'idiotical' locally under occupation. The Workhouse had six residents described as such, all originally from surrounding villages. By 1861, the term was 'imbecile', applied to two residents originally from local villages.

In 1871, the first year the census had a specific question, there were five 'imbeciles', four 'idiots' and one 'weak minded'. Of the ten in these categories, two were St Ivians.

The 1881 census showed four 'imbeciles', all from local villages. The 1891 census had seven 'imbeciles' and one 'idiot'. One was from St Ives. The 1901 census had five described as 'imbecile'. Four were from local villages.

The 1911 census showed two residents as 'imbecile' and four as 'idiot'. All these were described as 'from birth'. Two prevously had occupations, as a farm labourer and a cattle drover. One was from St Ives.

The following lists available details of the St Ives inmates in the St Ives Union Workhouse.

1871

William Simonds, a widowed 76 year old St Ives brickmaker, described as 'imbecile'. It's more likely William suffered from Alzheimer's disease.

Rachel Stocker was born in St Ives in 1829. In 1841, she lived with her father William, an agricultural labour, mother Rachel, and three sisters and brother in Taylor's Yard, St Ives. In 1851 Rachel was in the Workhouse, described as a 23 year old general servant, but with no health issues recorded. She remained there for the rest of her life, described in the 1871 census as an unmarried 44 year old labourer's daughter, 'idiot'. Rachel died in 1876, aged 50 years.

1881

Eliza Askew was a single 48 year old laundry worker, described as 'imbecile'. Eliza was born in 1843 in Nicholson's Yard, just off Back Street (today West Street) in St Ives. She was the youngest of five children, her father an agricultural labourer.

Eliza's father died in 1850. Her mother Elizabeth worked as a tripewoman to feed the young family. Tripe is an edible offal made from the stomach lining of cattle, pigs or sheep. Elizabeth cleaned, boiled and bleached the offal to prepare it for sale. It was a smelly occupation. Working as a pork butcher in the 1860s, Eliza's mother was again dealing in tripe by 1871.

Before 1871, Eliza had no occupation shown in census returns. In that year her occupation was 'helps ma'. The 1871 census added 'idiot from birth'. Eliza's mother had retired by 1881, aged 80 years. Eliza had no occupation. The census describes her as 'imbecile'.

After Eliza's mother died, with no one to look after her Eliza entered St Ives Union Workhouse. The 1891 census shows her occupation as 'laundry work'. It also describes her as 'imbecile'. The 1901 census describes Eliza as 'imbecile from birth'. Yet the 1911 census shows her occupation as 'domestic servant' and no infirmities. Maybe in her last years Eliza found her calling.

A 1915 Hunts Post article about Christmas festivities at the Workhouse (see under Laura Abbott below) specifically mentioned Eliza. She died in 1916 aged 73 years, after thirty-five years spent in the Workhouse.

1911

Laura Abbott was born in 1860 in Houghton, one of James' and Mary's nine children. Soon after Laura's birth, the family moved to Ramsey Road, St Ives. James was an agricultural labourer, out of work in 1871 when the family lived in Green Street, one of the poorest parts of St Ives. Laura was described as 'imbecile'. Although James was back in work as a brickmaker in 1881, the family still struggled. Their home was in Church Lane, originally called Poor Folk's Lane, possibly the most deprived part of St Ives. The family was still growing, Mary giving birth just three years before aged 47 years. The census described Laura as 'imbecile from birth'.

In 1888, the Cambridge Independent Press reported on a Charge of Rape on an Idiot in St Ives. The authorities accused Robert Thompson of Huntingdon of raping Laura just yards from her home. Thompson got off with the lesser charge of indecent assault through lack of evidence. In such cases defence counsel could take advantage of a victim's learning difficulties and claim the man was led on. The victim might not be able to testify. Laura gave evidence, although her mother had to interpret because 'the prosecutrix was very difficult to understand owing to a manifest impediment in her speech'.

In 1891 James worked as a gardener's labourer, the family living at 28 Victoria Terrace, Hemingford Grey. In 1901 James was still similarly employed, aged 70 years, with Mary and Laura at home.

James died in 1904, Mary in 1909. Without her parents for support, Laura moved into St Ives Union Workhouse. The 1911 census lists her as a 59 year old single woman, described as 'idiot from birth'.

The last echo of Laura is from the 1915 Huntingdon Post report Christmas Among the Poor, about Christmas festivities at the Workhouse. The article specifically mentions both Laura and Eliza Askew under the description 'perhaps forgotten by a good many, but well known in their generation, smiling a welcome as one approaches'.

Laura spent fifteen years in the Workhouse until her death in 1926, aged 67 years.

No comments:

Post a Comment