Gibbets in Huntingdonshire

For centuries, authorities displayed the bodies of criminals for public spectacle. The Romans tied or nailed their victims to a large wooden cross or stake. Left to hang, release by death might take hours or days. Occasionally, the body remained hanging after death. Fenstanton is the location of the UK's only example of crucifixion, found in 2021. A skeleton from the third or fourth century had a large nail driven through its heelbone.

In medieval England, spikes displayed severed heads. Some bodies were gibbeted. Encased in a metal cage, the aim was to display the rotting corpse for a longer period. In a few cases, the authorities gibbetted the victims alive. Following the Murder Act 1751, the bodies of those executed for murder were either given for dissection or gibbetted.

In the 70 years between 1720 and 1790 300 bodies were gibbeted, an average of 4 per year. Volume reduced thereafter until the practice was abolished in 1832. Gibbetting might have been small in number. But they were conspicuous in the landscape, a feature for decades. There are at least two cases of gibbetting in Huntingdonshire. The Norris Museum has part of a gibbet from one of these. Read on to learn more about gibbeting, and of the two local cases.

Murder Act 1751

By the mid 1700s, over 200 crimes carried the death penalty. Some were small misdemeanors, such as cutting down trees or pick-pocketing. Magistrates commuted many capital punishment convictions to transportation.

The Murder Act 1751 sought to inflict some extra punishment for the crime of murder. When the Act became law, the judge had discretion over the bodies of those executed for murder. He could either offer the body to anatomists for dissection, or order it to be hung in chains. There was no option for burial. In only 15% of cases did the judge order the gibbet. Since female bodies were in demand by anatomists, only men were gibbetted.

What was gibbeting?

An iron cage enclosed the murderer's body. This was suspended from a post as high as 30 feet or more. Often, nails studded the post to discourage theft or rescue of the body. Body parts were sought-after souvenirs. Relatives might seek to recover the body to give it a decent burial. The sentence for anyone caught tampering with the gibbet was 7 years transportation.

Displayed near to the scene of the crime, for greatest impact, the gibbet was visible from a public road. The gibbet cage was custom made. A blacksmith measured the murderer before execution. Usually, gibbetting took place on the day of execution, or soon after. Large crowds watched the execution and there was a carnival atmosphere. Many hundreds or thousands would view the gibbet in the following days.

Feature in the landscape

A gibbet might stay erected for decades. The body would slowly decay and weather. Small animals and birds would nibble at the remains. If gibbeted in a hot, dry summer, the corpse could mummify, turning dark brown and leathery. Gibbeted bodies stank. Nearby residents shut their windows to keep the stench out. Gibbets eerily clanked and creaked, twisting and turning in the wind, spooking people.

|

| Horse and rider spooked by gibbetted corpse. |

The location of a gibbet would change the local landscape. It became an important landmark, with new names given to roads and fields. Gibbets caused the creation of new routes. Sometimes to take travellers towards the gibbet. Or to avoid the spectacle.

The end of gibbetting

The practice went out of favour in the early 1800s. It was finally abolished in 1834. Authorities buried executed criminals within the prison precinct. 'Unclaimed' bodies of the poor dying in workhouses or hospitals supplied anatomists.

The last gibbet removed was in 1856, that of William Jobling at Jarrow Stake on the Tyne. Jobling was executed and gibbetted in 1832. His body disappeared within weeks, believed stolen and buried by relatives. It took another 24 years to remove the gibbet pole and cage.

Huntingdonshire gibbets

In 1787 GERVASE MATCHAM, aged 27 years, was crossing Salisbury Plain. Accompanied by an acquaintance, he suddenly saw a ghost. The vision was that of Benjamin Jones. So frightened was Matcham of the apparition, he confessed to a terrible crime.

Seven years earlier, Matcham had enlisted in the 49th Huntingdon Foot Brigade. Possibly he found their bright red uniform attractive. Benjamin Jones was a drummer boy in the Brigade. His father was the Quartermaster. He sent Benjamin on a 5 mile walk to collect £7 for supplies from Major Reynolds at Diddington Hall. It was dangerous to cross the countryside with a large sum of money, worth £1,000 today. Matcham accompanied the boy to ensure his safety.

On the return journey, the money tempted Matcham. South of Alconbury, they crossed a stone bridge over a tributary of Alconbury Brook. Matcham slit the boy's throat and fled north to York. There, he was press-ganged into the Navy. For 7 years, the murder of Benjamin Jones had gone unpunished. Until Matcham confessed.

Tried at Huntingdon Assizes, the magistrate convicted Matcham of murder. He was hanged for fifty minutes on Mill Common, Huntingdon in the red uniform of the Huntingdon Foot Brigade. The body was then cut down, carted to the location of the murder and hung in chains to rot.

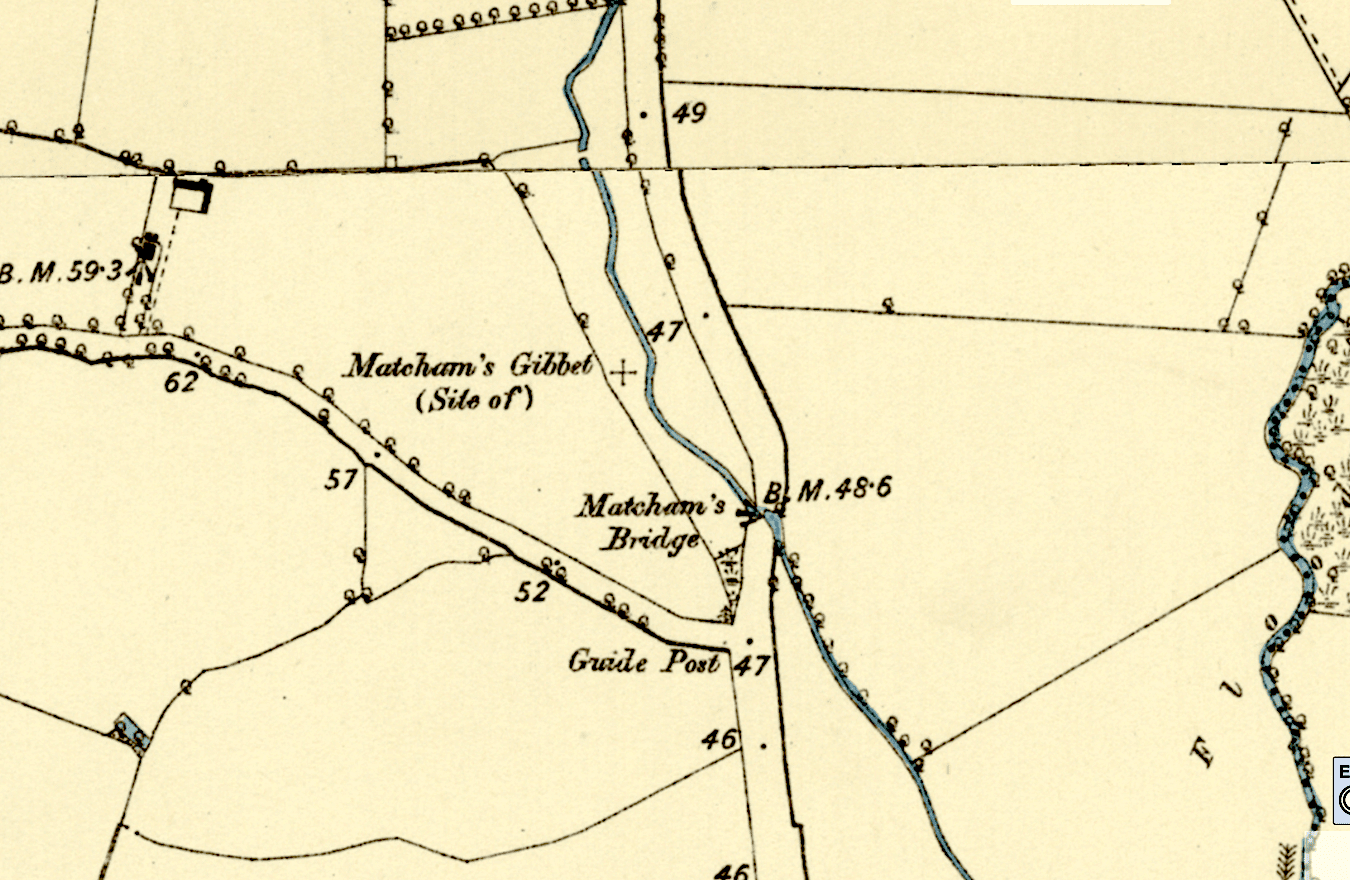

|

| 1887 Ordnance Survey map showing the location of murder & gibbet. |

The former ostler at a nearby inn remembered Matcham's gibbet. It was on rough ground next to the Great North Road.

Matcham's body was hung in chains, close by the road side, and the chains clipped the body and went tight round the neck, and the skull remained a long time after the rest of the body had got decayed. There was a swivel on the top of the head, and the body used to turn about with the wind. It often used to frit me as a lad. I have seen horses frit with it. The coach and carriage people were always on the look out for it. Oh yes! I can remember it rotting away, bit by bit, and the red rags flapping from it. After a while they took it down and very pleased I were to see the last of it.

Matcham's gibbet was taken down in 1827. This was 40yrs after his execution, long after his bones had decayed. In the 1920s, a low mound was still observable at the location. The Norris Museum has part of the gibbet cage.

In July 1795, JAMES CULLEY, THOMAS QUIN, Michael Quin and Thomas Markin lodged with William Marriot at Guyhirn, near Wisbech. The four were Irish transient agricultural workers in the area to help bring in the harvest.

On the evening of Friday 3 July 1795, the four men stole silver articles and one and a half guineas (almost £200 today). They fled the scene, leaving William, his wife and another lodger for dead having most inhumanely cut and treated. William Marriott survived for fifteen days, dying on Saturday 18 July 1795.

|

| Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 11 July 1795. |

The notice above was already published in newspapers when William Marriott died. The £40 reward could increase by up to £160 paid by authorities for the apprehension of all four murderers. This is equal to £20,000 today. All four were caught in Uttoxeter.

At the end of October 1795, the magistrate sentenced the men to be hanged. James Culley and Thomas Quin were gibbetted. Surgeons got the bodies of the other two for dissection. The two gibbeted bodies hung on a pole opposite William Marriott's house.

It was a mercy William Marriott's wife could no longer afford to live in the house. Without a husband to support her, she fell on hard times. To raise funds for Mrs Marriott, an account of the trial was published. It was advertised in local newspapers, shown below. The price of 9 pence is the equivalent today of about 3 pennies.

|

| Cambridge Intelligencer, 7 November 1795. |

In 1829, men digging for clay found parts of a skeleton three feet in the ground. The site was close to the gibbets' location. It was thought the remains were those of James Culley or Thomas Quin. The headpiece of one of the gibbet cages is now with the Wisbech and Fenland Museum. A flood washed away the gibbet pole.

No comments:

Post a Comment