Journeyman tailor

Apprenticeship started before the age of 14 years. Parents indentured their son to a master for 7 years for a fee. During that time, the apprentice tailor was bound to his master. Bad luck if your master was harsh. Attempted escape meant an appearance in court and gaol with hard labour. Supplied with bed and board, an apprentice got no wages.

|

| Interior of a tailor's shop, 1780. |

Tailors sat cross-legged on a bench while sewing, called the tailor's posture. A tailor's bunion was a common complaint. They sat for long hours with their feet rubbing against a hard surface. As a result, a painful bunion developed on the outside of their little toe. Tailors also suffered from the tailor's stoop, causing rounded shoulders from sitting bent forwards for long periods. Their eyesight suffered. Long working days involved detailed stitching in candlelight. Many tailors became almost blind.

Labour disputes

Once qualified, there was no security of employment. Tailors got work via a trade association named a call house. A journeyman tailor might appear to have a steady job. But he charged a daily rate and could be out of work without warning. The call house had no work for unreliable or poor quality workers.

Work was seasonal. There were heavy demands for clothing in winter, less so in summer. If there was no work for the journeyman tailor, he didn't get paid.

By the 1850s, conditions for journeymen tailors were at an all-time low. Cheap, ready-made clothing called 'slop' was freely available. Females worked on piecework from home or in sweatshops to make slop clothing. This was a much cheaper option to produce clothes. Tailoring was one of the first professions to experience labour disputes.

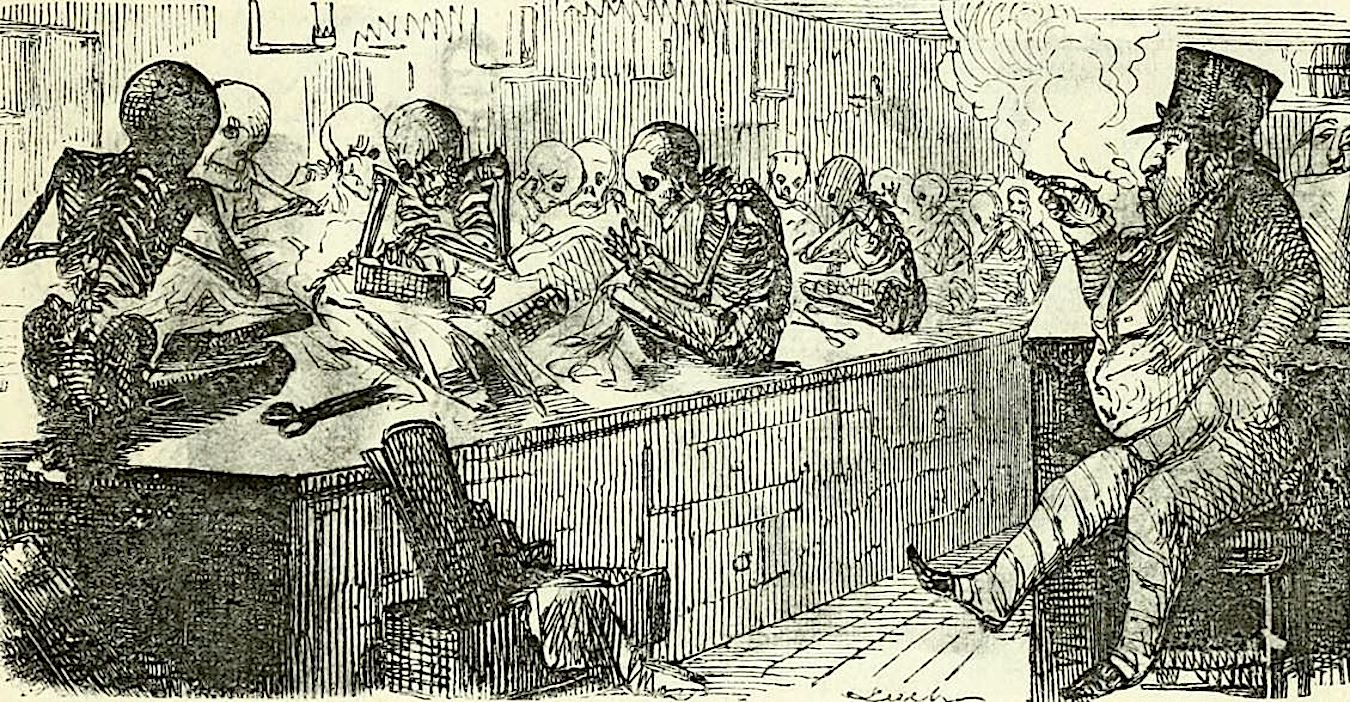

|

| Punch magazine cartoon of a slop clothing sweatshop, 1845. |

The St Ives Tailors' Strike

Cornelius Robinson was the largest and the highest quality tailor in St Ives, one of twelve. Cornelius informed his employees he was reducing their weekly wages from 21 to 18 shillings a week. This was just above the pay for a skilled farm labourer and a rate of less than 3 pence an hour for a 12 hour day. At times there was no work, and no pay. The men objected to the reduction and offered to settle by arbitration. Cornelius refused their offer.

The reason he gave for the reduction was the abolition of the Corn Laws. For 30 years to 1846, the Government kept the price of UK cereal grains high by imposing tariffs on imports. This benefitted land owners, but caused higher prices for the public.

Opposition to the Corn Laws argued by reducing the public's disposable income this hampered growth in other economic sectors. The Irish Potato Famine 1845-1852 was the final blow to the Corn Laws. There was a disastrous fall in food supplies. The UK needed cheap food urgently. The Government implemented a gradual reduction in the tariffs between 1846 and 1848. In 1849, the Corn Laws were removed.

With an influx of cheap imported grain, farmers had to reduce their prices. Thus, they had less money to spend on clothes. Cornelius argued he had to lower his costs. The real reason was Cornelius knew there were London tailors desperate enough for work to move and accept his reduced wages.

Six of his employees sent him a letter respectfully refusing his new terms. Isaac Muff, John Phypers, John's half brother George Stokes, Joseph Maund, William Pratt and Samuel Virgo Sharwood withdrew their labour and went on strike. The men worked for Cornelius on average for four years. John Phypers worked for Cornelius' father and grandfather. All but one man had wives and children.

Picketing

Described as 'proud and austere', Cornelius was no fool. He knew there were journeymen tailors in London desperate for work at his reduced rate. He bypassed the call house and advertised directly in London for tailors, stating 'full work and good wages'. Cornelius withheld that there was a strike.

The six men took action. Keeping watch at St Ives railway station, they confronted anyone who appeared to be a tailor. How did they recognise strike breakers? Many tailors had a peculiar gait, caused by their tailor's bunion or round shouldered tailor's stoop. The strikers also asked if there were any tailors present on the train.

Once explained there was a strike and the reason for it, the visitors usually returned to London. They were penniless and Cornelius had paid their fare to St Ives. The striking men offered to pay their return fare. By April it had cost £11 for return fares (today £1,000).

The strikers were banned from operating at St Ives station. They travelled to London and Cambridge to stop strike breakers getting on St Ives' trains.

The strikers called a meeting on 2 April 1850, reported in vivid detail by the Cambridgeshire General Advertiser. Held at the White Hart Inn, it almost descended into a riot. All six men were present and Isaac Muff spoke for 90 minutes, explaining their cause. The audience was sympathetic. The chairman put the question 'Whether the workmen had acted right or wrong' to the meeting. Nearly everyone held up their hand in support. Not a single hand was against. The chairman organised a collection for the strikers.

Charge with conspiracy

On 22 April 1850, all six men appeared in court on a charge of conspiracy. The specific charge was that they had 'unlawfully combined, conspired, and agreed to prevent (by persuasion and payment of money) men from working for one Cornelius Robinson, tailor and draper'. They pleaded not guilty. The magistrates referred the case up to the Huntingdon Assizes, a higher court. The Cambridge Advertiser reported on the case.

Working men in Cambridge were sympathetic to the strikers' cause. A public meeting invited Isaac Muff to speak about their strike. On 5 June 1850, 200 mechanics and artisans gathered together in the New Black Bear Inn, Cambridge. Isaac explained the position to them. He '... spoke with much ability. He is a pleasing orator...'. The Cambridge Independent Press reported on the meeting. The gathering collected £4 (today £375) at the door for the cause.

In July 1850, the six men appeared at Huntingdon Assizes. After evidence, the prosecution had a suggestion. If the men pleaded guilty and expressed their sorrow, they would not press for a judgment. The men agreed to this and walked free from court, bound over for £100 each to be on continued good behaviour. The Cambridge Independent Press reported the proceedings.

Outcome

It appears all six strikers moved away from St Ives soon after the strike. Three emigrated to the United States. Their work prospects in the local area and London were affected. Cornelius Robinson's business continued to thrive. Read on to learn about the life stories of each.

Isaac Muff and John Phypers

It's likely both John and Isaac were blacklisted for striking and work was difficult to find. In August 1850, the Cambridge Independent Press reported Isaac was planning to emigrate to the United States. A subscription was raised to help him.

Both Isaac and John travelled together with their wives aboard the Mississippi. Leaving London in late August, they stored all their worldly belongings in one box and one bag. They arrived in New York on 8 October 1850. Isaac and John were careful to maintain secrecy, listing themselves as labourers.

Isaac settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, over 100 miles south of New York. He never returned to tailoring, working as a storekeeper, retail dealer, then a janitor. Issac died in January 1883 in Norristown Insane Hospital, aged 62 years.

John was a St Ivian, born in 1817. After emigrating, he lived in Newburgh, 70 miles north of New York. Working as a gardener, by 1880 John had his own tailor's business, employing three men. By 1890, aged 83 years, John had retired and lived with his son in Cleveland, 70 miles west of Newburgh. He died in 1905 of old age, buried at Erie Street cemetery, Cleveland.

George Stokes

Half brother to John Phypers, George emigrated to the USA a few weeks after John. George arrived in New York aboard the Ocean Queen with his parents on 28 October 1850. Atlantic crossings were a risky business. In 1856 the Ocean Queen was lost at sea, with 90 passengers and 33 crew.

|

| Ocean Queen, 1851. |

Born in St Ives in 1827, George was the eldest of seven children. By age 14 years, George was a tailor's apprentice working for his father.

George followed John and settled in Cleveland. About 1865 George moved to Toronto, Canada. By 1871 he was working as a tailor, living with is wife and three children. George died in 1902, buried at Toronto Necropolis Cemetery.

Joseph Maund

Born in 1826 at St Johns Bedwardine, Worcestershire, Joseph was an apprenticed tailor at age 14 years, living at home. By 1848 Joseph was in St Ives. He married Sarah Everitt, and a son was born that year.

After the tailors' strike, Joseph and family moved back to his home village of St Johns Bedwardine. In 1851 he worked as a tailor. By 1861, he had a son and daughter. Another son arrived by 1871.

Joseph changed occupation by 1881. Aged 55 years, he worked as a market gardener.

Thomas, Joseph's eldest son, continued to live with his parents. Described in census returns as 'imbecile from birth' and 'idiot'. Joseph and his wife continued to care for Thomas until about 1900. By then, it was difficult for them to look after their son. They were in their 70s, Joseph in his 50s.

In 1901, Thomas was in Powick Lunatic Asylum. There were over 1,000 patients, with a ration of 1 to 10 nurses, attendants and servants to patients. To read about life in the 1800s and early 1900s in such asylums, click Imbeciles, idiots and lunatics.

Joseph died in 1910. His son Thomas died in 1916.

Samuel Virgo Sharwood

Born at Needingworth in 1824, by 1841 Samuel was a tailor's apprentice. He boarded with Henry Mitchel, tailor, his wife and 8 children at High Street North, Somersham. In 1846 Samuel married Elizabeth Jackson in St Ives. It's unclear what happened to Samuel after the tailors' strike.

William Pratt

Born at Richmond, Yorkshire in 1826, by 1847 William was in St Ives. He married Mary Harrup in that year.

After the tailors' strike, William stayed in St Ives. He started up in business himself. In 1851, he was a tailor master living in Crown Street with his wife, son and father in law in 1851. It appears he moved away from the area after this.

Cornelius Robinson

Born in St Ives in 1819, Cornelius came from a family of tailors and drapers. Working for his father, Noble Robinson, in 1836 they advertised Cornelius' return from London, '... after receiving valuable instructions in the art of cutting from one of the fashionable and practical cutters in the West End...'

In 1842 Cornelius married Nancy Johnson. The same year he took over the business and announced his return from London with '... a choice assortment of superfine cloths, fancy waistcoats, and trowsers (sic) suitable for the present season.'

After the tailors' strike, Cornelius' business continued to thrive. In 1851, he employed nine men. A daughter was born in 1852. By 1861 Cornelius and Nancy lived at West End with two servants. Cornelius had another string to his bow. He was an insurance agent, the Hail-Storm Insurance Company's representative for St Ives.

Cornelius gave up tailoring by 1881, aged 62 years. He had an insurance office at The Quay and lived in London Road with his wife and a servant. Cornelius died on 25 December 1896, aged 87 years. He left an estate of £10 (today under £1,000) to his wife.

No comments:

Post a Comment