Drover

St Ives depended on the weekly livestock market for its prosperity. It was the second biggest such market in England, after Smithfield, London. And the market depended on drovers. They herded livestock from as far away as Ireland. Once sold, St Ives drovers moved the livestock to London.

If you had a choice of occupation in the 1800s, who would choose to be a drover? When few people travelled far from their homes, you were away for long periods. Exposed to the elements by day, you might have overnight accommodation at some tavern. More likely you spent the night under the stars. Exhaustion, hunger and thirst were the norm for both drover and beasts. One description from 1884 was a weary caretaker of weary beasts.

The apprenticeship was long and hard. Routes had to be learned by heart without signpost or map. You must find water. But the job was well paid. And what an adventure!

London and other cities depended on the drover. A prodigious appetite for beef and other meat needed a steady supply. Read on to learn what life was like for a drover, and about St Ives drovers.

Origins

Cattle were herded around England for millennia. Romans drove livestock to feed their soldiers. Weekly cattle markets developed from 1200. St Ives' own more general market started in 1110.

As London and other cities grew, they relied on a steady supply of livestock for food. By the 1800s Londoners spent more on beef than bread. Consumption of beef was 4 pounds of beef a week, about four times the rate of the average American today. In 1853, the estimate was 14 million livestock per year coming into London.

Some arrived in a sorry state. In a hurry to get tired beasts to market, even the slight incline on the new Blackfriars Bridge was too much for some. In 1873 a reported commented in the early hours of the morning I have often seen scores of jaded cattle, lying down in all directions, exhausted after the long Sunday tramp. In 1884 The Lancet reported It is a pitiful sight in London to see sheep being driven from the market, and one or more of the flock lagging behind for the chance of a drop of water in some stagnant gutter, and, lacking this, to see the poor animal fail altogether, and lie down, or rather fall down, for very weariness.

|

| A cattle drove creating havoc in Park Lane, London, late 1800s. |

A farmer cannot both take care of animals on a farm and take stock on a long journey to market. So the owner would entrust his stock to a drover. The farmer needed a high degree of trust. The drover not only delivered the stock to market in as good a condition as possible. He also brought back large sums of money.

The drover also had to trust his master. In 1832, the Old Bailey convicted Henry Wells of stealing two heifers and a mare. Henry pleaded his innocence. He claimed he had merely been employed as a drover to move the beasts. Unknown in London, the Old Bailey sentenced Henry to be executed. Although Henry's sentence was commuted, he faced transportation to Australia. When news reached the court from his home in Hertfordshire of Henry's 40 year unblemished character, the judge set him free.

A drover's life

Drovers followed traditional routes. Many had organised sites for overnight shelter and fodder for animals. Some inns and pubs catered especially for drovers, with grazing available. In 1830, the Red Lion public house near Royston advertised every accommodation may be had for drovers stopping on their way to town, any number of cattle can be taken in, during the whole of summer. The address was near the 47th Mile Stone on the old north road.

If in the open overnight, a makeshift shelter would suffice. A drover might kick one of the resting beasts up and away, to take advantage of the warm spot left behind. The journey would last from a few days to months. Some drovers rode horses, others walked.

A drover took care of the stock so they were in good condition on arrival at market. But that was not always the case. Some drovers treated their livestock cruelly. In 1835 at St Ives market a poor bullock, harassed and tormented by those monsters in human shape - "Drovers", took refuge in the shop of Mrs Robinson, milliner. In an 1837 report of a Bluntisham man fined for mistreating a horse at St Ives market, the magistrates stated they would make an example of anyone mistreating their stock, to check the brutality which is witnessed in that place every market-day.

|

| Drovers beating cattle at market. |

Droves averaged about 100 beasts. In 1797, 10 drovers took 400 cattle from Scotland to Bath. Trying to get that number of animals through a tollgate would be difficult. It's likely such large groups split into somewhere near 100. They gathered together again at the end of the journey.

Cattle were shod with iron shoes if they had to travel over hard surfaces. Sheep, geese, turkeys, pigs, horses and goats were also driven to market. Geese and turkeys might be driven through a pan of tar mixed with sawdust and grit to protect their feet. Up to 150,000 turkeys travelled from East Anglia to London each year. The journey took 3 months.

A dog's life

Drovers relied on their dogs to nip and harass the livestock along the right path. A dog also discouraged predators at night. Many a dog patiently awaited his master outside a public house. One dog, given wrong instructions when the man staggered out, ignored his master and calmly herded the sheep in the right direction.

The drover’s canine companions were tough. Once the drove completed, the dog might be sent home while the drover enjoyed a short break. The dog would retrace his route home. Innkeepers or farmers provided food on the dog's return journey. The drover paid for that food on their next trip.

Sometimes, dogs didn't wait. Having reached the market, they turned on their paws and ran. Using their noses alone, they returned to a home as far away as Scotland or Wales. Days before his master returned, the dog would be resting by the hearth.

|

| A drover and his dog. |

One case records a cattle purchaser who thought he'd have the drover's dog too. Along the route, the dog got free. Aiming to return home, the dog assumed if he'd been stolen, so had the cattle. The dog faithfully herded the cattle back to his master.

Decline

Increasingly through the 1800s, droving declined. Common land was enclosed. Farming became more intensive. Transit through countryside the stock had passed for hundreds of years was more difficult. Available grazing areas reduced.

By the 1850s, a national rail network was in place. Rail transport meant cattle could go to market within days rather than weeks. Initially, drovers travelled by train with their cattle. They herded their unwilling beasts into wagons and moved them to market at the other end. The drovers slept in the last carriage, the brake van. In 1860, the mail train from Scotland struck a cattle train south of Atherstone station. All nine Irish drovers asleep in the brake van were killed.

From 1865 rinderpest spread across England. A highly contagious disease, it killed millions of cattle. Its impact on the livestock industry was devastating. In the 1870s, the Government passed laws licensing drovers. Their animals had to be inspected for disease. These regulations made droving more expensive and time consuming.

The last recorded cattle drove across Wales was in 1870, and for sheep 1900. A cattle drove took place in Scotland in 1906.

Droving in St Ives

St Ives livestock market was second only to Smithfield, London. Every Monday, over 12,000 cattle, sheep, horses, pigs, goats, chickens, geese and turkeys entered the town centre. The population of St Ives was 3,000.

Cattle sold in the Broadway backed up Ramsey Road and along St Audrey's Lane. Horses were sold in Back Street, today East and West Street. Sheep gathered in Sheepfold. Pigs squealed in Pig Lane. The town council sold rights to gather the prodigious amounts of manure. This was cleared from streets Monday evening for use on allotments and fields.

Livestock sold at St Ives market came from as far away as Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Before market day, cattle grazed in the water meadows surrounding the town. One old resident recalled falling asleep on Sunday evenings to the sound of lowing cattle in Hemingford Meadow.

Where can you see a drovers' road locally? Medieval drovers' roads were wide, over 20 yards across. On either side were wide grazing verges. Ramsey Road was a main route into St Ives for livestock driven from the north. It follows the same route first mapped by Pettis in 1728. Above its junction with St Audrey Lane there are wide margins. Walk up Old Ramsey Road, above the modern bend in the road added for accident prevention. Imagine the removal of the tarmac road, replaced by dirt and rubble. With wide grassy margins for grazing, you're walking an ancient drove road.

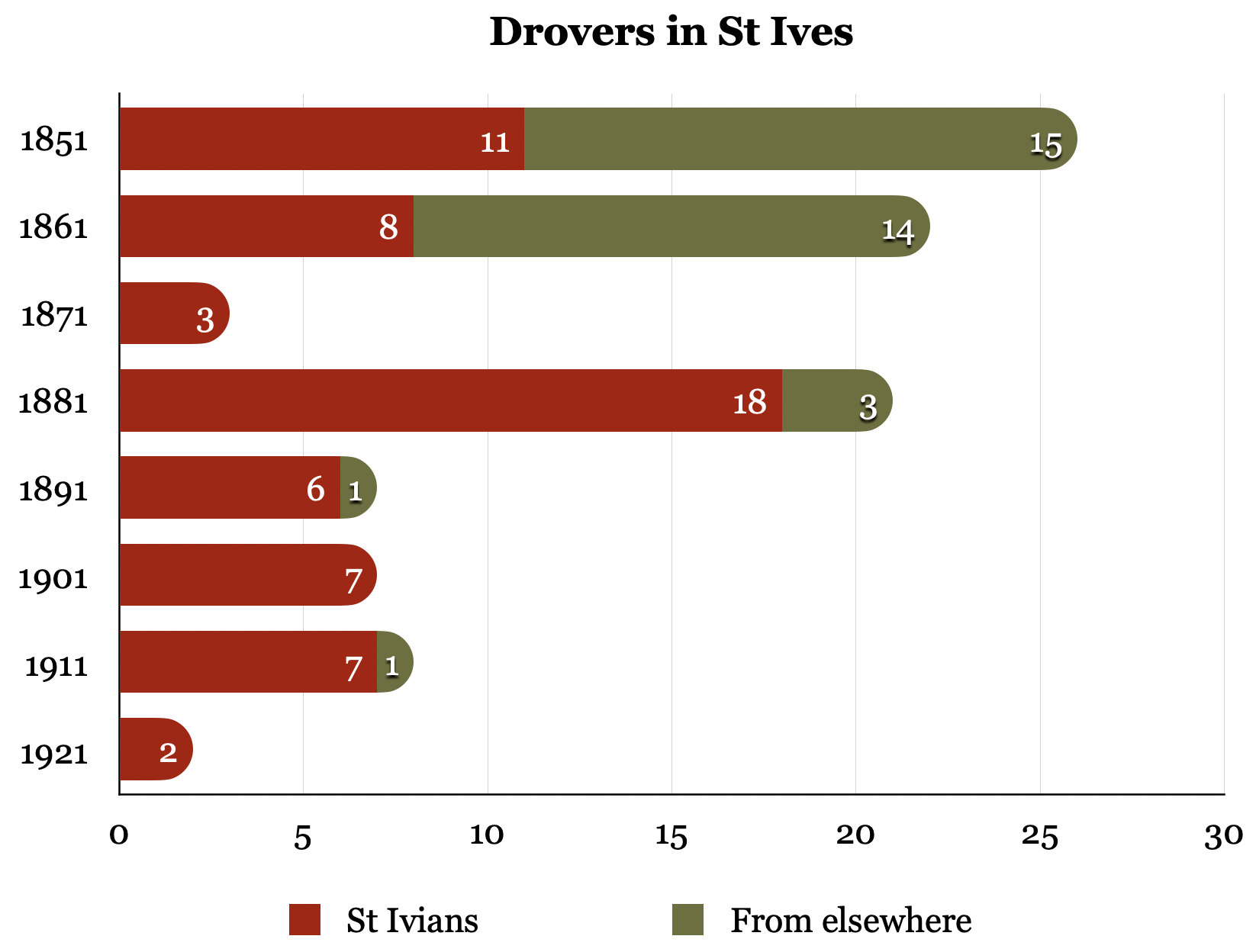

The graph above uses census returns to show the number of drovers in St Ives on a Sunday, before the Monday livestock market. The St Ives railway transported livestock by 1850, so the graph includes the effect of railway carriage.

In the early years of 1851 & 1861, there were more drovers from elsewhere than St Ives' own drovers. In the decade from 1870, the population of Huntingdonshire reduced by 10% because of agricultural recession. Workers sought employment in urban areas. The number of livestock in Huntingdonshire fell by 20%. Caused by falling grain prices, rising costs and bad weather, it had a devastating effect on livestock sales. This explains the low number of drovers recorded in 1871.

The 1921 census took place in late June, delayed from April because of the threat of a general strike after coal miners withdrew their labour. The coal miners' strike lasted until July and had a major effect on rail transport. The low number of drovers in the 1921 census reflects the inability to transport livestock to markets.

Not all visiting drovers stayed in St Ives. Surrounding villages offered cheaper accommodation. The Woolpack at Fenstanton was a popular choice. In 1851 there were 6 drovers from elsewhere lodging there, 5 in 1861.

St Ives drovers

Not all drovers were men. Some fiercely independent women also drove livestock. The 1851 census records Mary Ann Smith from St Ives, a jobbing drover. This meant she was self employed, taking droving jobs when available. Aged 44 years, Mary was a widow and head of household at 33 Sheepmarket.

Here are the life stories of three St Ives drovers.

ROBERT OFFLEY

Robert reflected the drover's fate in the latter half of the 1800s. He not only drove pigs and cattle, but was also a pork butcher and hawked trinkets. Sometimes Robert was reduced to vagrancy, begging as he tramped along.

More commonly known as Holy Moses, Robert also preached in the tradition of Jane Hawkins, a prophetic rhymer. Robert added song. Sometimes his rhymes were worldly and topical. As he approached a row of cottages or a farmhouse, Robert would start singing. He did this to see if there were any unfriendly dogs around.

|

| Robert Offley, 'Holy Moses', c1900. |

In a 1953 Bedfordshire Times newspaper article readers remembered Robert from the early 1900s, dressed in filthy rags, with unkempt hair and a long beard. Despite his forbidding and pitiable appearance, he always smiled.

Most beggars were disliked. Robert was an exception, fondly remembered by many, otherwise tolerated, because of his natural gifts and unusually cultivated character. He was described as an old rascal, a fifty-fifty mixture of craftiness and sagacity, stocky of form and grinning like a jinn, ready-witted and cheerful, his smiling eyes could break through a cold greeting.

Although remembered as always smiling and happy, the fate of Robert's children was dark. To read more about his life, read some of Robert's rhymes, and learn what happened to his children, click Robert Offley.

JOHN BINGHAM

Recording his date of birth in census returns anywhere between 1816 and 1823, the only certainty is John was born in St Ives. In 1841, aged 20 years, he boarded with his sister, aged 15 years, at Wyton. John worked as an agricultural labourer. In June 1841 he married Amelia Stutters from Cambridge.

The couple moved to a small cottage in Seekings Lane, a narrow alley running from the Waits to Back Street (now East Street), no longer existing. Daughter Emma was born in 1846. By 1851 John worked as a drover. Another two daughters arrived, Elizabeth 1852 and Harriet 1855.

John was one of those drovers who didn't spare the beasts in his care. In 1856, magistrates fined John and Levi Allsop for cruelty at St Ives Monday livestock market. Levi was fined 12 shillings for cruelly beating a beast at the market. John was the worst of the two, fined 20 shillings (today £80) for using the beast very cruelly generally. John wasn't averse to treating his fellow drovers roughly either. In 1864, he was summoned for assaulting James Sutton, also a drover. The men settled the case out of court. In 1872 John was fined 24 shillings (today £100) for cruelly beating a dog.

By 1871 the family moved to the Bullock Market, today The Broadway. Two teenage daughters still lived at home. On the evening of the census, 5 year old granddaughter Fanny was staying with her grandparents.

|

| The Monday Bullock Market, late 1800s. |

John still worked as a drover in 1881, aged 65 years. John and Amelia lived alone. The image above, taken just before the opening of the new market at the other end of town, shows how congested the Bullock Market (The Broadway) was on Mondays. Buildings and passersby needed some protection. A few enterprising residents erected posts and railings for a fee. John was one of these. When cattle sales moved to the new market in 1886, John was out of pocket. St Ives Town Council paid him the staggering amount of £100 in compensation, today equal to £10,000. There's no further record of John after 1886.

HECTOR ROWELL

Called Mike in drover and drinking circles, Hector was born in Bridge Street, St Ives, in 1857. His father, James, was a busy man, one of only two veterinary surgeons in a town which saw the influx of over 12,000 livestock every Monday. The family employed two live-in female servants. In 1861 tragedy struck the family. Both James and second eldest child Harriet died, cause unknown.

In 1871, the family lodged at the Star, still in Bridge Street. A public house up to 1870, the Star was now a lodging house. Hector's mother, Juliana, gave music lessons. Eldest daughter, 18 year old Sarah, worked as a dressmaker helping to support the family. The remaining children, six in all, had no occupation.

This included Hector, aged 14 years. Typically boys would be working as early as the age of 10, and the family no doubt could do with extra income. So why were Hector, and Henry aged 16 years, not working? More mysteriously, the two youngest children were born after James passed away. Possibly Juliana was pregnant with Clara, aged 9 years, at the time of James' death. But Elizabeth (called Bertha), aged 7 years? The family could no longer could afford servants.

Hector worked as a cattle drover by 1876, aged 19 years. In that year he appeared in the Priory Road court, charged with stealing a half pint of beer, value 1 penny. The charge was withdrawn on payment of 5 shillings.

In 1879 Hector was in more serious trouble. The Kings Lynn Petty Sessions charged him with defrauding the Great Eastern Railway. Hector had ridden on a train from Kings Lynn to Ely without a ticket. Henry was not present in court. A letter from Louisa was read out explaining Hector was not at home when the summons arrived and was therefore unaware. A telegram from Hector was also read to the court saying he'd only arrived home that morning and couldn't get to the court in time.

Whatever Lousia said in her letter, the magistrates decided it was practically an admission of guilt. The prosecution stated this wasn't the only time Hector had ridden without a ticket. Hector had been overheard in a pub boasting he could do what he liked on the Great Eastern line. Hector was found guilty and fined 5 shillings, ordered to pay the fare of 3 shillings, and charged expenses of £2 1 shilling or a month in gaol. This total is equivalent to £250 today.

By 1881, the family had moved to Vicar's Row, a narrow alley running from the Waits. All the children still lived with Louisa, other than Henry. To add to the family's hardships, eldest child Sarah, aged 28 years, had turned blind. None of the five daughters, aged from 28 years to 17 years, had an occupation. Neither did Louisa, shown as Veterinary surgeon's widow. Hector, aged 24 years, was the only one in work, as a cattle drover, presumably supporting the whole family.

Alcohol was a constant problem for Hector. In October 1881 he was fined 21 shillings (today £100) for being drunk. In 1882 Hector and William Cook of Fenstanton were fined 8 shillings and bound to keep the peace for 3 months for fighting in the streets of St Ives. In 1885 Hector was fined 12s 6d and costs for being drunk and riotous in the public streets of St Ives. In 1887 a performance of Professor Andre's Alpine Choir in the St Ives Corn Exchange was stopped whilst organisers ejected Hector and another man after a slight disturbance. Hector was described as a disreputable character. In December 1887 Hector helped old lady who had fallen from the railway bridge back home. He was described as the worse for drink.

Hector married Mary Bennet from Hemingford Abbots in 1884. In 1891 they lived in Priory Road. Hector's occupation was a general labourer. With them were two young cousins aged 10 years and 8 years. By 1901 Hector and Mary had moved to 2 Cumberland Place, St Ives, a two up, two down cottage in a close leading off East Street. Hector still worked as a general labourer, but was self-employed. He was back to work as a cattle drover by 1911.

Mary died in 1917. By 1921 Hector was an inmate of St Ives Union Workhouse. Aged 68 years, he showed his occupation as casual cattle drover. Hector died in 1922.

No comments:

Post a Comment