.jpg) |

| Archie in a sailor's uniform, 1905. From an autographed postcard. |

Today, people working in entertainment are twice as likely as the general population to experience depression. It was even tougher in the 1900s, when music hall audiences were rowdy and readily showed their appreciation or contempt. There was a history of mental health problems in Archie's family and Archie himself was a troubled soul. Did he foresee the decline of his profession, a series of family tragedies tipping him over the edge and leading to his death? Read on to learn about Archie's life, how his star briefly shone bright, his most popular compositions and the rise and fall of the British music hall.

Early life

Born in 1878 at Hemingford Abbots, Archie's father was Ebenezer John Naish, his mother Ada Clarke. Both parents were musically inclined. Archie's younger sister, Persis Sarah, was born in 1880 and grew up to become a music teacher.

Ebenezer was a published poet before Archie's birth. His book of poetry Herbert Maxfield and other Poems was published in 1874 and gained the review: If Mr Naish can write so well at twenty-one, we may hope to hear of greater achievements in the future. Ebenezer was a grocer, as was his father. Soon after Archie's birth, the family moved to Bridge Street, St Ives, living over their grocer's shop. That remained Archie's family home for the next twenty years.

Archie inherited his father's poetic turn of phrase, but put it to different use. Writing amusing monologues and songs, he soon became popular locally as an entertainer. As Archie's confidence, skills and repertoire increased, he used the railway network to travel further afield.

In March 1897 aged 19 years, Archie was one of several excellent artistes from St Ives who appeared at the Bedford Liberal Association's annual gathering. The review commented A musical sketch "In the Country," by Mr. Naish was very funny... The following year Archie performed at Harleston, Norfolk. By July 1899 Archie was looking for a seaside booking. He advertised in The Era for a fortnight's holiday engagement, as Entertainer, original sketches and whistling solos, good references.

In January 1901 Archie appeared at a Grand Concert in Bedford. He performed a musical sketch The Poets Redemption, an amusing imitation of a person with a poetical mania. For a follow up, Archie whistled the song Killarney. A review said Too much praise could not be bestowed on this clever performance. Every note whistled was perfectly clear, and in the pianissimo verse not one faulty note could be detected. He added musical sketches In the Country and The Village Pump.

In April 1901 Archie appeared at Cambridge Guildhall at a concert. The review said Mr Archie Naish was a great favourite with his original sketches. He was down for two items, but so well did he perform that the the number was increased to four. Mr Naish appears to have a natural bent for humorous sketches, and he kept his delighted hearers in continual laughter with his funny sallies and clever imitations. Cambridge concert-goers will wish to see him upon the platform again.

At the end of each performance he returned to the family home in Bridge Street, to his main occupation as a grocer's assistant, working for his father. In his early twenties, Archie was still an amateur entertainer.

The Great British Music Hall

The origin of music halls was in 1700's taverns and coffeehouses that provided entertainment as a supplement to food and drink. From the 1850s, the acts became the focus in music hall theatres developed to provide affordable entertainment to a working class with more leisure time and money to spend. A more relaxed and jovial atmosphere with plenty of alcohol meant a raucous, even rowdy, experience for the performers. If the audience liked the songs they would join in. Anything lack-lustre was booed off the stage.

There was a wide range of performances, from singing and dancing, comedy, even acrobatics. By 1875, there were 375 music halls in Greater London alone. Big stars performed in several venues each night. That meant high earnings, but also high stress.

After WWI it was soon apparent music halls were in decline. Jazz music gained popularity, aided by cheaper gramophones. The BBC began radio broadcasts in 1922. Silent cinema developed from 1910, to be overtaken by talking films from the late 1920s. Television broadcasts started in 1936, the final nail in the coffin for the Great British Music Hall.

|

| Archie Naish, 1909. |

Archie turns professional

The first reference to Archie living in London is in a promotion for the Cambridge & County Liberal Club Musical Society annual concert in March 1905, in which he is billed as Mr. Archie Naish (London), Musical Entertainer. Prior to this Archie had increasingly appeared in and around London and the south coast, mentioned in newspaper reviews regularly. So by this date it seems he had turned professional.

In 1906 Archie appeared in a ballad concert at the Temperance Hall, Derby. The review stated Mr. Archie Naish concluded each part of the programme with a humorous sketch. He is a very clever society entertainer, sings and plays admirably, and is genuinely funny and quite refined at the same time. He burlesqued Handel's methods in a piece of which the theme was "Let go, Eliza," and showed his knowledge of current events in his "Come to glorious Sunlight, 15 ounces to the pound," while his "Air Varie" justified its name by his singing "Oh, dry those tears," to the accompaniment afforded by "We won't go home till morning." Mr. Naish will be heard again with pleasure.

Positive reviews abounded, generally appearing weekly, as Archie travelled throughout England. In 1908, appearing at the Forester's Hall, Canterbury, the review wrote Mr. Archie Naish, the well-known humorist, made a great hit with his musical sketch at the piano in which he represented the preparations for a pageant. So greatly were this talented gentleman's efforts appreciated that he was enthusiastically encored.

In 1909, Archie organised four other entertainers, billed as Archie Naish's Vaudeville Company, to appear in a series of summer concerts held in Montpellier Gardens, Cheltenham. The Company was short-lived, Archie back to solo performances later in 1909.

Pressure to create

As Archie became more well known and his novelty wore off, reviews got shorter and less glowing. Critics tended to read and reuse comments made by their peers for previous appearances. So Archie's material was becoming known, not just to critics, but audiences as well. Archie would be listed among the entertainers without comment, or as Archie Naish, a smart entertainer at the piano. Glowing reviews became the exception. There was an increasing pressure to continually come up with new sketches and compositions.

There were the occasional highlights. For an appearance at The Gem Palace, Yarmouth, Archie was billed as Mr. Archie Naish, World Famous Society Entertainer. A review of his performance at the Reading Gardeners' Association stated Mr. Archie Naish, in his humorous sketches at the piano, showed his mastery of the instrument, and also provoked the risible qualities of the company in a very marked degree. But there was also the review of an appearance at The Pier, Skegness, Mr. Archie Naish, entertainer at the piano, is too well know to our readers to need any words of commendation. His reception was sufficient evidence of his popularity.

In 1910 Archie rented two unfurnished rooms at 98 Great Russell Street, London. The following year he lived in three rooms at 106 Great Russell Street, London. His occupation was Entertainer at the piano. Archie had a 30 year old boarder, Douglas William Thorburn, manager of a newspaper. It appears Douglas, who in 1901 lived with family in Fenstanton, was an old friend.

In 1912 a review of the Epping Forest Musical Society smoking concert mentioned Archie as the popular humorist delighted the audience with his amusing versions of "Hush-a-bye, baby" and "The Girl behind the Bar," and acknowledged two determined encores by singing "Jonah Man" and "The cabby waiter," the latter creating roars of laughter and giving birth to another encore, in reply to which Mr. Naish gave an extremely funny account of a pianoforte recital.

A 1913 review of Archie's appearance at the Birmingham Grand noted his songs at the piano are agreeable if not exciting.

Archie in crisis

In 1915 Archie gave himself up at Harrow Road police station on a charge of indecent assault occurring when he appeared at Newquay, Cornwall. The circumstances of the assault are unknown. What did hit the headlines was his attempted suicide while in his cell. Found rolling on the floor with a neckerchief wound three times around his neck and tied tightly, when freed by the station sergeant, Archie said I feel my position, but you were too quick! I was not strong enough. It was a weak attempt.

In spite of the suicide attempt, Archie continued performing. Disc records, later called 78s, became a popular way of listening to music in the home from 1910. One of Reynold and Co's series of 1916 Concert Party Albums included The Night Light, a song composed, written and sung by Archie which included harmonised chorus. A review mentioned The humour is of the healthy type, and the music savours of that catchy, haunting order which always spells success.

Records were still considered a novelty. In the early 1900s, most home musical entertainment was at the piano or other instrument. Sheet music easily outsold records. All Archie's most popular songs were published as sheet music. For either record or sheet music, Archie received a one-off payment.

Archie was still drawing laughs with his preparations for a pageant, more than eight years after first performing the sketch. There was an unrelenting pressure for new material. The alternative was playing to new, often smaller, audiences who hadn't heard his material. Archie could still generate requests for multiple encores when he appeared at club and society events, as at the 1919 gathering for the return of the Oxted war heroes and the Hitchin Symphonic Society's concert. But there is no published work after 1917.

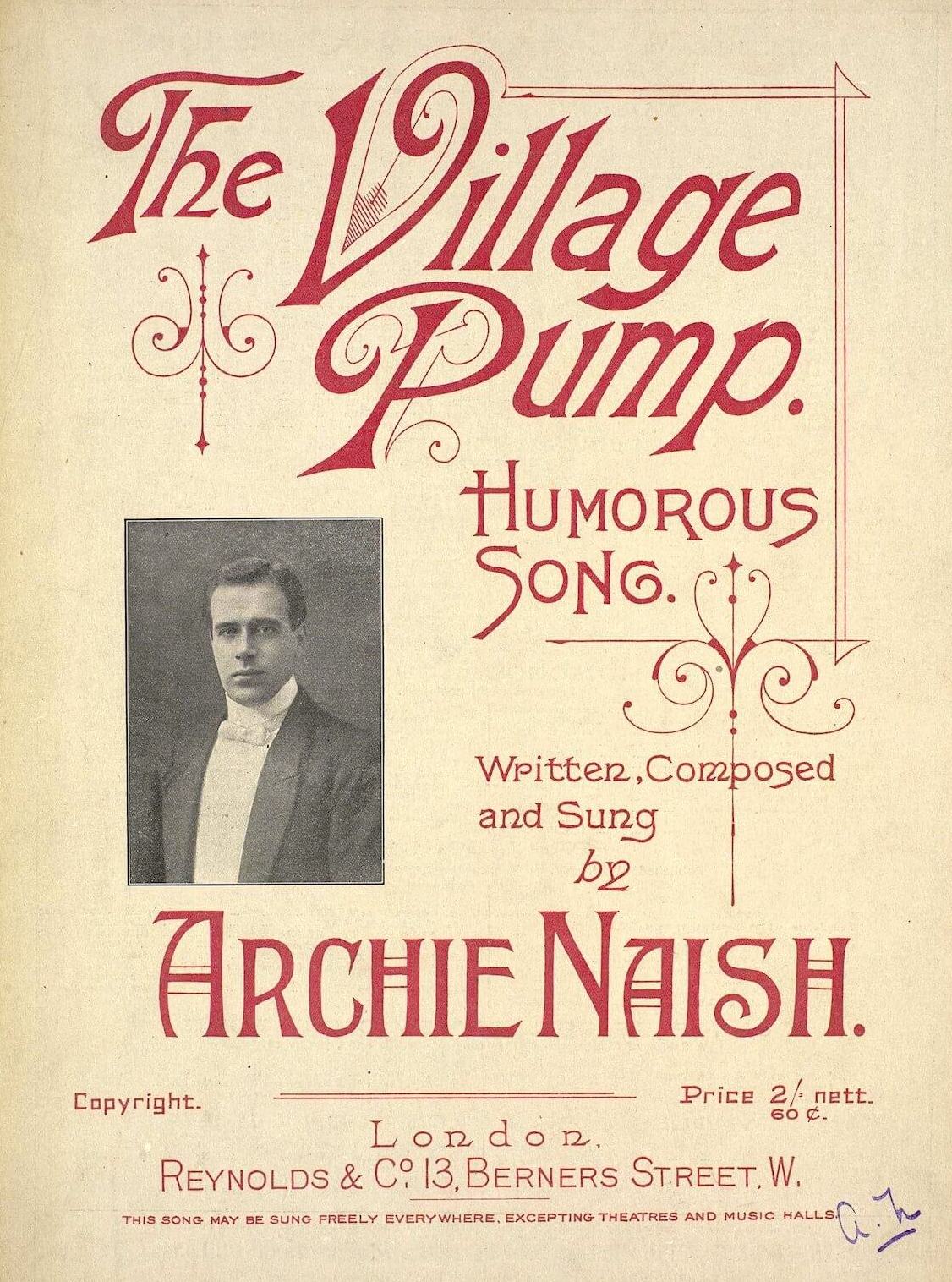

|

| The Village Pump sheet music cover, 1905. |

Family tragedies

Archie's mother died in 1920, aged 65 years. In 1921 his father was in Three Counties Mental Hospital, where he most probably stayed for the rest of his life, until 1932 when he died there aged 80 years. His sister died in 1922 in Cambridge County Asylum, aged 41 years. Archie was deeply affected by the close deaths of his mother and sister.

Throughout the summer of 1922 Archie appeared at The Globe, London, merely billed as 8.30 pm Archie Naish and a piano. This was a thirty minute warm-up act to the following comedy play Belinda at 9.00pm starring Irene Vanbrugh. These were Archie's last stage appearances.

The Peterborough & Hunts Standard reported Archie's tragic death on 29 April 1923. The Westminster Coroner judged Archie had committed suicide whilst of unsound mind at his home at 96 Cambridge Street, Lupus Street, Pimlico, London. He climbed out of his bathroom window, passed over a greenhouse and dived head first into his garden. It was believed Archie was depressed following the death of his mother and sister and had been suffering from insomnia. Archie was in a good financial position, but there was a history of insanity in the family. His father had been committed to an asylum, and Archie himself had been a patient in a mental hospital.

Archie's effects were valued at £846 (today £41,000). He left everything to Francis Puttrell Woods, a solicitor's clerk of St Ives. Archie is buried in Hemingford Grey cemetery with his father.

Archie's catalogue

Between 1906 and 1917 Archie had twenty works published, listed below. The Village Pump featured on the BBC Radio programme The Archers and is still sung by traditional singers throughout England.

After his death, other compositions quickly fell out of favour. There are only six mentions in newspapers of his songs or monologues being performed after his death, the last being in 1956. An example is that from the 1937 Coventry Evening Telegraph. Under the heading Story Behind the Song the article wrote One of the most haunting and exquisite lullabies in the language was penned by a famous song-writer of his day as a direct tribute to his mother. The writer was Archie Naish, and the love between mother and son was of an outstanding quality long after he had attained man's estate. It was to her he took all his doubts and difficulties, with her he shared all his successes. And it was the recollection of the days when as a child she used to croon him to sleep that he penned a lullaby that will long live. This was possibly The Night Light.

The following were the most popular, click any to view the lyrics. The date of publication is shown in brackets. This is not necessarily the date of composition. Archie's earliest published songs were written in his late teens in the 1890s as he acquired local popularity as a performer. For example, he performed The Village Pump in 1901.

The Employment Bureau (1906)

Sybil (1909)

The Village Pump (1910)

Won't You Waltz With Me? (1910)

Hush-a-bye baby (1912)

The Night Light (1916)

Other compositions were as follows. The lyrics to these are not known.

The Lady Palmist (1908)

A Tale Untold (1910)

The Duck Pond (1912)

Do I Love my Love? (1912)

Would I Were A Fringe Net (1912)

How Many Beans Make Five? (1914)

Made in England (1914)

Phyllis (1915)

The Band Played On (1916)

On a Sunny Sunday Afternoon (1916, music by Archie, words by Clifford Grey)

I'm 94 Today (1917)

Why Don't They Knight Charlie Chaplin? (1917)

Very Likely (1917)

The Girl behind the Bar (1917)

No comments:

Post a Comment